Area of Interest

Maryon Park History

The Graphic October 1890: “On the recommendation of the Parks and Open Spaces Committee, the Council accepted with thanks Sir S. Maryon Wilson’s gift of twelve acres of freehold land in Charlton parish, but near the populous part of Woolwich, as a recreation-ground to be used by the public in perpetuity, under the control of the Council.”

London Daily News. 27th October 1890: “Opening of the Maryon Park,– The new park which has been given to the inhabitants of Plumstead and Woolwich by Sir S. Maryon-Wilson was formally opened on Saturday afternoon, under circumstances which were not altogether cheerful. Some preparations had been made to celebrate the event by the people of Old Charlton, but the banners which were stretched across the line of the route and hung from many of the windows looked hopelessly forlorn in the pitiless rain. A string of carriages containing the local magnates were drawn up outside the railway station awaiting the arrival of Sir John Lubbock, who was to take over the park from the donor on behalf of the London County Council. When all was ready the procession moved off, headed by a body of bandsmen, who showed by the vigour of their performance a determination to make the best of the situation. A drive of a mile or so brought the visitors to the park, which is an odd-looking place, not unlike a quarry, except the sides are grass-grown instead of being bare. It lies in the hollow, just behind the Woolwich Dockyard, and is surrounded by hills which will form a delightful recreation ground for children in the summer time.

On Saturday the place was anything but delightful, for the clayey ground was so much soaked by the rain that the escort of volunteers who were mounting guard before the reception tent stood ankle deep in mud.No time was lost in getting through the ceremony here, Sir S. Maryon- Wilson handing the key of the park to Sir J. Lubbock. The company drove after wards to the Assembly Rooms, where the subsequent proceedings were carried on at greater leisure and certainly with more comfort.”

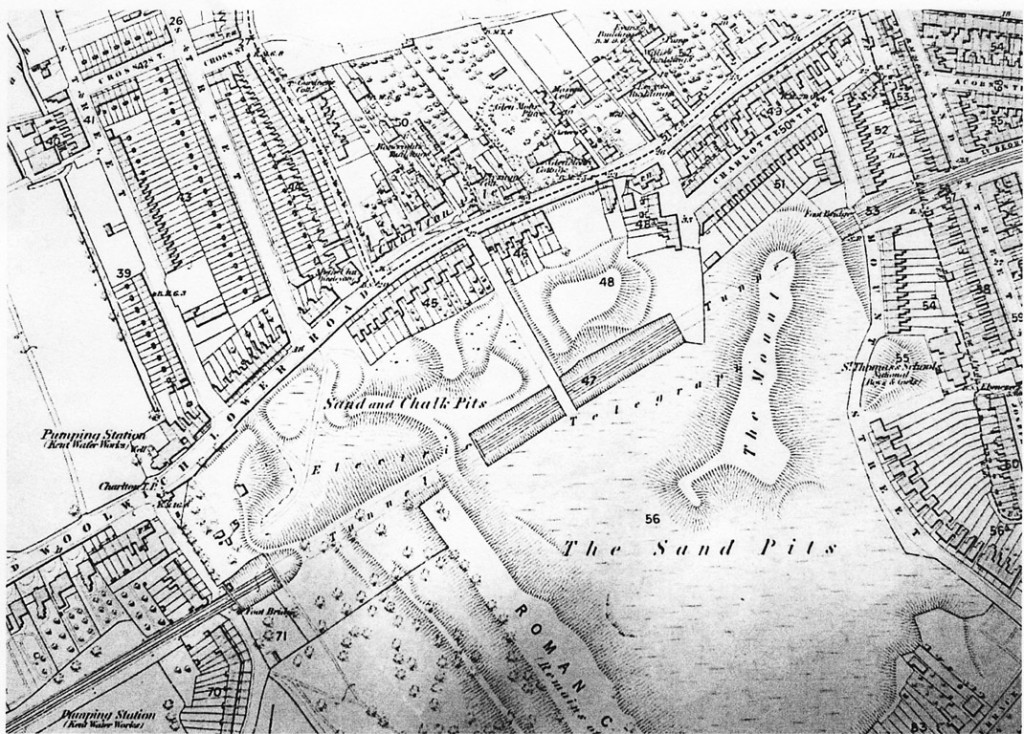

A potted history from John Smith, The History of Charlton, 1970 “In 1889 Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson 10th Bt (Editor’s Note: “I believe he means Sir Spencer Maryon Maryon -Wilson 11th Bt.”) presented 12 acres of land to the LCC to become Maryon Park. It was the site of a worked out chalk, sand and gravel pit, including Cox’s Mount (qv). The new park’s entrance was in Mount Street, now closed. It was leveled off, grassed over and opened to the public on October 25th 1890 by Sir John Lubbock on behalf of the LCC. Handsome triumphal arches were erected by the inhabitants for the occasion, one at either end of Charlton Village, and another spanning the entrance to the Park……..

The grass area at Maryon Park was too restricted for cricket to be played, although one of the conditions of the gift was that the boys from the training ship ‘Warspite’ which lay at anchor off Charlton should be free to play. Five years later Sir S.P.Maryon Wilson (Editor’s Note: Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon-Wilson) presented one third of an acre more land for the formation of an open air children’s gymnasium with an additional entrance in the Lower Woolwich Road. Kentish Independent Aug 1895.

The following year a handsome iron bandstand replacing the 3-year old rustic one was also erected, and over £4000 spent in general improvements, including a keeper’s lodge and toilets.

In 1908 the L.C.C. for £500 purchased an additional five acres of the disused sand-pit from the Maryon-Wilson estates, following a further gift of two acres from Sir S.P.M.Wilson.

The Opening of the extension to Maryon Park, 1909. Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon-Wilson. London Metropolitan Archives.

This portion of the Park which included Maryon Mount and provision for another entrance from Maryon Road provided a larger grass area. Sir George Alexander, Chairman of the LCC Parks Committee performed the opening ceremony in the presence of Sir S.P.M.Wilson in December the following year. Kentish Independent 1909.

An additional three acres were purchased in 1925 when Hanging Wood Lane – now Thorntree Road – was widened. This also allowed a southern entrance to the Park by a flight of steep steps. Another eight acres were purchased four years later, to make a total of thirty.

Apart from regular band concerts, etc, the Park was also the venue for the first LCC (London County Council) Open-Air Theatre when the 300 year old Earl Armstrong Repertory Company was invited to perform, and in 1907, a salute of 21 guns by the R.A.(Royal Artillery) was fired on the occasion of the King’s birthday.”

A further account: G.L.Gomma, Clerk of the Council, London County Council, December 1909.

“Among the works, which have been carried out, in connection with this recent extension, is the formation of a new path leading from Woodlands Terrace to the land which has been presented. This path connects the top of the cliff with Maryon Park by means of a steep winding walk, with rustic steps in places. The old park fence has been re-fixed with the necessary additions on the new boundary line.

On the land which has been purchased, a considerable amount of rustic fencing has been necessary at the summits of steep slopes, which without such protection would be dangerous and speaking generally, the surface of the ground has been by leveling and filling up holes where necessary, adapted for its intended purpose.

A new entrance has been formed from Tamar Street into the eastern portion of this land.

The works have been carried out by the Parks Department at a cost of about £800 under the supervision of Lt. Col. Sexby, the Chief Officer.

The key which the opening ceremony is performed is of iron and has been designed and made by Mr. Leonard Richards, a student of the L.C.C. Camberwell School of Art and Crafts.”

Some ‘known’ facts

The mount at Maryon Park was formerly used as a semaphore station in communication with that at Shooters Hill. The Mount and the surrounding area was rented in 1838 form the Lord of the Manor by a gentleman named Cox who lived at 5 Charlton Terrace, for ‘cultivation and recreation’. He built a summer house for entertaining his friends.

The Mount was also used by the Admiralty for adjusting ships compasses and after 10 years it was moved to Maryon Road where a small observatory was built.

When Maryon Park was being laid out, workers found the foundations of an old kiln which had been used for burning red bricks. A deep well had been sunk by the Lord of the Manor near the lodge to help in the process of making the bricks.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Lee Beasley remembers when the Council had its own nurseries.

Did the parks department, at one time, grow their own plants?

We did. We did use to grow our own plants – some of our own – except the plants we use primarily are Alternanthera, which comes in a range of colours which is, you know, red, green, purple, pink…

Certainly when we had our own nurseries at Well Hall Pleasance… the Pleasance nurseries went in about ’88. We used to grow plants there and then, in ’86, when the G.L.C. was absorbed into the respective boroughs and Greenwich took on Avery Hill Park it absorbed the nurseries there, which were the main supplier to the whole of the G.L.C. actually, in terms of bedding, and the council ran them for a few years and we used to grow some of those plants as well as all our other bedding plants in those nurseries but, unfortunately, the nursery had to close down. It wasn’t economically viable and I think in maybe about ‘89/’90 the nursery was handed over to a private tropical plant provider on a lease kind of arrangement from the council. So we now buy all of our own plants.

When did the nurseries in Maryon Park close down?

Again there was a small nursery there before my time so certainly I would hazard a guess as the early seventies.

That early?

Yeah, that’s my understanding. I haven’t got any other memory of that.

Do you know if that was as a supplier for Maryon Park or wider…?

I don’t know is the answer but my feeling would be that when I was first started working in Greenwich we had a number of small nurseries as well as the main nurseries and, whilst they did supply for, you know, the local vicinity what we would do is grow a batch of particular plants in a particular nursery and they went borough-wide so there’s every likelihood that many of the plants in Charlton Park, Maryon Park, Maryon Wilson Park and Hornfair Park would have been grown in Maryon Park, yeah.

So different nurseries grew…?

Generally grew different batches of plants, yeah. It’s just economy of scale… there’s the logistics to doing that.

How do you feel about not having nurseries?

I think from an educational perspective it was always a really good educational opportunity for apprentices and that kind of thing. Financially I don’t think it’s a wrong decision because I don’t think it’s viable for a local authority to compete with commercial nurseries that can grow these plants on such a massive scale so cheap but certainly from, you know, the interest point of the staff and the education for the apprentices and it’s a nice association to have I think as well… for that localism, yeah? And there’s an opportunity to control as well more than when you can when you’re buying in from… but commercially I think it was the only decision.

Interview Extract: Paul Martin comments on relatively recent changes to use of Maryon Park

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

Has it changed how it’s used? I’ve been here twelve years now. There’s been more of an influx of migrants into the area so over the weekends… in the summer… it’s become more multi-cultural. There’s much more eastern European families and Africans. So I’ve seen that really increase, which is lovely. Different cultures using the park, particularly of a weekend. I’ve seen that, you know. The anti-social behaviour I’ve managed to… I can manage, you know. I can manage that, you know.

Do they use the park in a different way… east European and African people?

They’re absolutely fine. Do they use the park in a different way? Eastern European is predominantly male and it’s football, football-based. But it’s quite intimidating actually because on a Saturday or a Sunday, when the weather’s really nice, there could be as many as – I took some pictures to show my old manager – I bet there’s as many as eighty, I think I counted eighty males all around the bottom green there. So it’s quite intimidating but they’re absolutely fine. I’ve seen a couple of punch-ups amongst them but they sort that out themselves. But they’re mainly focused around football. And they’re very respectful towards me. I can’t say I’ve had any problems with them. There’s different religions as well. Muslims and Asian families using the park more which is great. It’s a real multi-cultural setting in the summer… ethnic backgrounds, you know. It’s lovely.

Audio Extract: Paul Martin talks about relatively recent changes to use of Maryon Park

The filming of Blow Up

Extract from Interview Transcript: David Sneeth sees the filming of Blow Up.

(An edited audio version version of this extract may also be heard below.)

You remember Blow Up being filmed?

Yeah we used to go there every day while it was being filmed – a lot.

What did you see?

I don’t remember seeing any film cameras at all. I remember the facades that were put up on the houses. Yeah, in Woodland Terrace. Pal of mine lived in a house that had one of the facades at the bottom of the garden. I remember going down to the park, there were milling about, there was virtually no security which looking back seems a bit strange but we went I there – I think it was probably made 1966-ish. I would have been about 13, it would have been made in the summer ‘cause I remember good weather. The other thing that sticks in my mind is the mound – where it was filmed on top of – we went up on the outside and the so-called body was lying in the bushes and I know we got shooed away because they must have been filming… only time we got shooed away –casual about it. It was great. Didn’t see any of the stars, didn’t see the tennis match. Saw the mini-moke they drove around in. I think we saw a couple of the clown-type people – couldn’t be sure of that. The steps which I think Hemmings runs up – they’re the other end of the mound going down towards the gate at the bottom – they were filming outside the gates at the bottom going down to the bottom road to Woolwich, as you went out the gates, the right hand side, there was a greengrocers and they took it over and turned it into a junk shop. I can always remember, he bought the propeller in the main window of the shop. We went all round there. I can remember waiting for them to start filming but they never did. Saw preparations. Can’t remember full blown movie gear.

What did your friend think of the façade?

He was 13. Not fazed, not at that age. Very relaxed, no hassle.

Went to see it as soon as it came out. The park keeper was in it. You see Morris Walk being built. She was in it, as I said she was a misery. Used to wear these brown tweeds and a fedora. Didn’t have a summer uniform and she looks as if these tweeds are really heavy on her in the film. I think they picked her out because she looked so downcast.

Audio Extract: David Sneeth remembers the filming of Blow Up

Extract from Interview Transcript: Linda Walker has her lunch interrupted.

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

I was working in London and the job I was working at – I got fed up with traveling so I decided to try and work locally, temp agency, just doing, working at one of the factories – AEI along the Lower Road, there was a whole load of factories. At the bottom entrance to the park, the one with the tennis courts, there was a little shop on the left and when Blow Up was being filmed they turned it into an antique shop, the little shop which sold biscuits, groceries. As I was walking up the road to go and eat my sandwiches I was jostled by all these people. I thought, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ because normally there wasn’t anyone – my escape, getting out of the boring job by having lunch in the park. I got jostled by all these people who were quite luvvie people and I turned round to see who jostled ma and it was Vanessa Redgrave! I thought, ‘Who do these people think they are?’ and they thought, ‘What are these people doing here?’ and it was my regular lunch time thing! I carried on walking into the park and then I was told I couldn’t have my lunch in the park and we all had to get out because the park had been booked for filming, which extremely pissed me off I must say. It was amazing to see the film Blow Up after that happened . I’ve seen the film twice – they had a screening in the park last year I think, I went with a friend, screening in the park – brought it all back to me. I’ve been involved in going to that park for years with my children.

Did you know it was Vanessa Redgrave immediately?

Did you know it was Vanessa Redgrave immediately?

I turned round – you jostling me – I could see they were all luvvies darling and stuff like that. I just turned round and I thought, ‘Shit, that is Vanessa Redgrave.’ I’m a great film person. I love films. I don’t know what I had seen her in before that. ‘That is Vanessa Redgrave!’ I looked around at all the others and was they were film types. When the film came out I was absolutely sure about it.

You weren’t able to stay and watch the filming?

No we were told to get out – I was really annoyed – pay my council tax in Greenwich, why should we be turned out? No couldn’t stay and eat sandwiches. We had to get out – they were filming. As you go up that little slope there was a field where the body was so they didn’t want loads of people around – that’s near the entrance to the field, that’s where the body was found and then of course it disappeared. I used to go years after when my children were born, had picnics and tell them.

Audio Extract: Linda Walker has her lunch interrupted

Extract from Interview Transcript: Paul Tiffen remembers a bit of a shemozzle

Before I moved up to Maryon Wilson they were putting scaffolding up, round near Tamar Gate – several places they were putting scaffolding up for the cameras to do their shooting from and I knew that Sophia Loren was in the country making a film at the time. I thought that would be nice, Sophia Loren coming locally, and then they said, ‘It’s going to be Vanessa Redgrave.’ I thought, ‘Who’s Vanessa Redgrave?’ Anyway, I moved up to the top park and it hadn’t been shot then. I remember going down to the bottom park one day to pick up something. I was talking to some guys up near the top lawn and the gates were open – the double gates there – and a white Rolls Royce drove in and David Hemmings was driving and Antonioni was with him. And the foreman at the time, Les Cooper, he was a book man, he went by the book. ‘You can’t bring that car in here. You can’t drive around. This is not a public… take it out.” And there was a bit of a shemozzle there. I didn’t see the finale of it but I remember David Hemmings coming and this white Rolls Royce is actually in the film.

I remember Vera. In the opening shot there’s a park keeper, a women park keeper, picking up paper, down near the railway. Down near Tamar. And that was Vera. I knew Vera. She was an actual park keeper. I think she got £5 for being in that shot. But, actually, I’m sorry to say I thought it was one of the most boring films I’ve ever seen.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Ann Foster watches the filming of Blow Up.

They made the film Blow Up – the beginning and the end of the film Blow Up, which was David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave, in 1966. So, when we lived in Denmark House in Maryon Road, I was on the fifth floor and we could overlook the park. And we could overlook the top lawn, which as children we were never allowed up there because it was a big, grassy area with bushes and it would be a place that you actually in your own mind would think, ‘Well, I’m not going up there because everything overhangs.’ I think there was four different ways you could get to the top lawn.

And then they came along with this film crew. I’d only been married… I got married in 1964. We could see all the filming because high up, we could look over onto that top lawn. We couldn’t see all of it but you could recognise David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave and there would be all the cameras. Then they would come down and they would have their vans and their canteens. So that was about the only thing I ever watched from the park, from my flat, but we always had a good view anyway.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Paul Stephens makes mischief at the filming

(An edited audio version of this extract can be heard directly below this.)

I was about fifteen years old at the time. I believe it was 1965 because the film came out in 1966. The school I went to was Charlton Secondary School, which is now a college. We used to – very naughtily – what was called ‘hopping the wag,’ which was leaving school without the teacher knowing it. And they were filming Blow Up in Maryon Park, opposite Charlton Secondary School and numerous young people used to go and try and get involved with the filming.

We climbed up to the top of Maryon Park, where there’s a green at the top, where they filmed the dead body in the park. Now, what happened was, we got behind the chestnut fencing while they were filming it and they cut a big branch down and stuck it in the middle of the green. And I do believe the man’s name was Ronan O’Casey. So they asked Ronan to go and lay down behind the tree to act as the dead body while they took still pictures. And us, being very naughty schoolchildren… when he lay down, they said, “Ronan, lay down,” we were shouting out, “Okay, Ronan. You can get up now!” So Ronan got up and they were shouting and screaming, “Why are you getting up?” He said, “You told me to get up.” They said, “We didn’t,” because they were quite a long way away from him and he could only hear us. So they asked him to lay down again. So he lay down again. They said, “Right, we’re shooting.” We said, “Ronan, you can get up now.” So Ronan got up again. By this time the photographers and Ronan realised it wasn’t them shouting it out so we got chased round the park about three times and that was one story which was quite funny.

And when you’re sitting behind the chestnut fencing you can hear everything that was being said between the actors because they couldn’t see us because we were behind the bushes. So where they were organising parties and Vanessa Redgrave was talking to Ronan O’Casey, I tend to remember – there was a party going off in Chelsea somewhere and that all sounded very, very interesting to a bunch of Charlton boys, that were fifteen years old.

Now, the second part of my story was Vanessa Redgrave was wearing a checked shirt and the next day, after we’d been chased across the park, the next day I ran across the green while she was sitting there getting some make-up put on or just watching the filming, I can’t remember. And I rushed across to get her autograph. The bouncers – for the use of the word – tried to get hold of me but she said it was ok for me to get her autograph. I said to her, “At the end of the filming could I have your checked shirt, please?” And she said, “Certainly, if you come and ask for it.” But I never got me checked shirt, so I’m still waiting.

Audio Extract: Paul Stephens disrupts the filming

Audio Extract: Mal Gallaghy reflects on the cult of Blow Up

Woolwich Road: Blow Up – Scene 14

Google ‘sites/blowupthenandnow.com’ and you will find yourself in an intriguing website called ‘Blow Up Then and Now’ produced by Ian Bolton. It contains many interesting photographs of scenes from the film including Maryon Park, Woolwich Road and Tamar Street.

…The film BLOWUP (1966) has always fascinated me, ever since I first saw it as a young teenager back in the mid-1970s. Maybe it was the fact that I was alone and got to choose my own programmes for the first time (my parents were out whilst I babysat my young sister), and I got to see scantily-clad beauties cavorting with David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave without her vest on.

Or, maybe I was just taken-in by the green-ness of Maryon Park, the red-ness of the Stockwell Road, the blue-ness of the Woolwich Road, the white-ness of the mimes’ faces, or any number of other visual and/or atmospheric tricks and devices utilised by the enigmatic Michelangelo Antonioni and his team of film-makers…

Ian S. Bolton: June 2003

Putting

Extract from Interview transcript: Ron Roffey pays thruppence to putt.

We paid our thruppence. There was a little hut, a green hut, with two, I suppose, open hatch doors.

You open the bottom and open the top. I suppose it was a stable door really. The park-keeper sat in there with his container, with his putting sticks on his little desk. He had a table and a wooden box with balls in. You could select your stick and some of them had quite heavy heads, some of them had very light heads and he would give you a ball. You used to inspect your ball very carefully. Then you would trot out, just across the path, down five or six steps onto the putting green because it was below the level of the path. In fact, people used to sit on seats around the path and watch the people play putting. The objective was you had a white marker and you popped your ball down and there was a hole that had a little flag in it with a number… Number 1… and you putted off. You hit the ball with your stick. The objective was to get it in the hole in the less number of strokes.

Some of the holes were long, some were short. There weren’t any dog-leg holes because they were all nice and straight, beautifully maintained and you were also given a scorecard, a white scorecard with the number of the holes and a little line and you put the number of strokes you did and at the end you totted up the number of strokes and if you did three for each hole, i.e. fifty-four strokes, you’d done pretty well.

You just paid your thruppence and at the end of the eighteenth hole he was keeping his beady eye on you in case you didn’t go round for a second time, as some of us young bloods tried on occasion. But no, he stood there and you just walked up the steps, gave him your stick, gave him your ball… “Thank you very much,” and that was it.

Audio Extract: Ron Roffey remembers the park during the War

Courting

Extract from Interview Transcript: Ann Foster remembers her sister courting.

When my sister was fifteen, she met her husband. She met him because we still always used to – that was our main thing – was to go up the park, not actually to maybe meet boyfriends but we would go up there because it was mixed, boys and girls. My sister went in there one day and there was a big putting green and tennis courts and she said to me, “See that man over…” well, she classed him as a boy… “See that boy over there talking to that man by the putting green?” She said, “He looks nice. I’m going to go over and talk to him.” So I said, “Are you sure, because the park could be shutting soon.” She said, “Yeah, I’ll be ok.” So off she went and I went home. I don’t think people sort of said, “Come on, you’ve got to come home now.” So I came home with the other girls and the boys and then my sister turned up about an hour later and she had this boy in tow. Come in. “Oh, Mum,” she said. “This is Graham. I’ve just met him up the park and he’s brought me home because he was worried that I had to walk alone because Ann had already gone.”

So, anyway, he came in and my Mum wasn’t a one for making people cups of tea. You sat down but you didn’t get… Mum wasn’t getting up and making tea. Mum thanked him very much and he said to my Mum, “Could I please take your daughter out?” And my Mum said, “Well, she is still at school. She’s only fifteen.” And he said, “But I will take good care of her because I’m…” – I think he was twenty-two, and he said – “I’ve been in the RAF and I know she will come to no harm.” So Mum said, “OK. That’s fine.” And she said to me, “It’s a shame you can’t meet someone like him.” Because he’d come from Devon and he was living in Maryon Road, in lodgings.

So I said to Sue, “How comes you got him to bring you home?” So she said, “I just said to the park-keeper, ‘What’s the time?’” And he said what it was and he said, “We’ll be shutting in a minute.” Well, my sister knew that and then Graham had said, “Well, how far have you got to go?” And that was it. Then as soon as my sister left school, at sixteen, she got married and moved to Devon. Fifty years later she’s still married. But my sister put her eyes on him and she made up her mind.

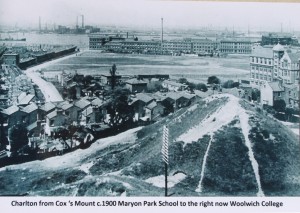

Cox’s Mount

John Smith, History of Charlton, 1970 Vol. 3 page 216

“Maryon Park was presented to the LCC by Sir S. Maryon-Wilson in 1890. It consisted of 12 acres and contained a large hillock, known as Cox’s Mount. Mr Cox, who lived at 5 Charlton Terrace, had acquired it in 1838 on a short lease, erected a summerhouse on the summit, planted poplars and invited friends to come and view ships passing on the Thames.

From 1845 for 15 years, the Admiralty rented Cox’s Mount from Sir Thomas Maryon-Wilson for 4s per annum as a station for correcting ships’ compasses. In 1860 this was moved to Maryon Road to a small laboratory. In 1866 the Mount was in use as a Coastguard station. Later a bonfire was held on it to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1891.

By the late 1920s the mount had been reduced by erosion, mainly due to children sliding down it. It was fenced off and became overgrown with trees and shrubs. During World War II it was used as a lookout point by the Home Guard.”

Extract from Interview Transcript: Ron Roffey remembers getting into Cox’s Mount.

There was the rings and a see-saw and a number of swings, as I say, right up the far end that had a fence that was fenced off because you’d almost reached the railway cutting. Between the fence and the railway cutting there was a garden. The gardens were always beautifully kept. There was an entrance there to what we used to call ‘Cox’s Mount.’ Now you couldn’t get into Cox’s Mount because it was fenced off by some chestnut fencing that was about seven foot high. So the chestnut fencing went from the fence from the swing park across to the iron railings that stopped you getting onto the railway line, that went down in the cutting. So there was that little area about fifty by twenty-five that was grass and just not looked after but there was this very tall chestnut fence that stopped you getting onto Cox’s Mount.

Well, some of my friends that went to Maryon Park, of course, all lived on the Woolwich Road. So traveling from Maryon Park going towards Greenwich – those tall houses that were three storeys – a lot of the children went to those schools and, of course, those houses backed on to Cox’s Mount and they went all the way along to Charlton Lane, Holy Trinity Church and, as I say, lots of those houses they had a wall that kept them – that stopped them, you know, the end of their gardens, and there was a flat area at the bottom of Cox’s Mount, there was a garage halfway along from Maryon Park as you walked along towards Greenwich. There was some houses and then a garage that seemed to do repairs and then there were houses and all those houses backed onto Cox’s Mount and there was a level area behind those houses. Sand, of course, that must have been about (I suppose) fifty or sixty yards long and about twenty-five feet wide and we used that as a football pitch.

So we had access to Cox’s Mount via some of the children that lived in those houses. But of course we had also another entrance – we could get in through the church. There were railings around the church and there was a railing from the side of the church to the first house and there was one of the metal spikes missing so we used to squeeze through there, go through the church gardens and then hop over. Again the spiked fence from the church to Cox’s Mount and we were there. So we had all sorts of ways of doing things.

Gilbert’s Pit was over the other side that ran behind Pound Park Road and up Charlton Lane. Of course, that was great because we used to not only play football but we used to dig… make camps in there and dig into the side of the hill. When I think about Health and Safety now, I mean some of these things just fell in because the sand was so fine. You know, there was the danger of being… but it never occurred to us! We just dug into the side of the hill and made a little camp in there.

Audio Extract: Ron Roffey remembers Cox’s Mount in the 30s

View from Cox’s Mount c. 1900, contributed by Jim Free

The postcard shows New Charlton and Charlton Vale. The typical ‘School Board for London’ is Maryon Park School, opened in 1896. The road running towards the river is Hardens manor Way with the ‘Lad of the Village’ three storey public house about half way down on the left.

The pub was renamed ‘Thames Barrier Arms’ after the Thames Barrier opened in 1983. It now houses a vets practice. The large factory on the riverside is Siemens Brothers Telegraph Works. Behind the factory can be seen the masts of the training ship ‘Warspite’.

Dancing and the Bandstand

Extract form Interview Transcript: Maggie, Elsie and Bettie, at Minnie Bennett House, remember the bandstand.

Maggie: Maryon Park’s got three entrances, ain’t it?

Elsie:Yeah. You’ve got the one in the main road… in the Lower Road.

One up the top as you come out of Maryon Wilson. You can cross over to that one and then there’s one round the back where the bandstand used to be.

Elsie: … Whether the bandstand’s still there I don’t know.

Betty: It would be interesting. I couldn’t do it because I couldn’t go down all those steps now. I’d have to go round the bottom way.

Elsie: There was a lot of steps, wasn’t there?

Betty: Yeah, and go through the bottom way.

The bandstand isn’t there.

Elsie: No, that’s gone.

Maggie: That’s gone out of Charlton… out of Maryon?

Out of Maryon. Yes, that’s gone.

Betty: What have they got there now? Anything or is it just…?

They’ve still got the tennis courts and then the rest of that flat area is just grass and I think people play football there.

Betty: Oh, that would be quite nice.

Doris… she said she used to go dancing there.

Betty: Yeah, we did.

You did as well?

Betty: We all did, didn’t we? Jitterbug round the bandstand.

Elsie: In the park, round the bandstand. That’s when the bandstand was there, yeah.

Betty: On a Sunday night, yeah.

Elsie: That’s right.

Betty: That was lovely. It used to be packed.

We’ve found photos of people doing country dancing.

Betty: Oh, country dancing… yeah. We used to have… we used to really love those nights, didn’t we?

Elsie: Yeah.

Betty: When it was a nice summer’s evening.

Extract from Interview transcript: Ron Roffey remembers dance bands during the War

I was nine when the war broke out but I remember those dances. I must have been a bit older I should have thought. I must have been about thirteen at that time, fourteen… but I do distinctly [remember]… and they were so well attended and the number of people that were dancing. It was a real congregation of people, you know.

And this was outdoors?

Outdoors? Oh, yeah. At the far end of Maryon Park, where the head park-keeper had a lovely house, a beautiful house. Next to his house were the toilets and then there was this great are – paved area… tarmac – with this lovely bandstand in the middle. Something akin to the bandstand in Greenwich Park, you know. Beautifully constructed and on the other side, opposite the house, there was a public shelter, like you see at the seaside, with benches that people could sit and then all around the edge of the putting green like a sweep, a segment of a circle, there were all the seats. You know, the metal seats that people sit on. They’re wooden-slatted and elderly people or the people that didn’t want to dance sat there all around and some people sat along the path by the putting green just listening to the music. And it was very, very well attended.

What sort of music was it and who was playing it?

Oh, it was modern music. You’re talking about World War Two stuff, you know. Not quite ‘In The Mood’ but all the modern, the American stuff that came in, and of course, in those days there was the old-fashioned stuff for the older ones. You had like the Waltz and the Valeta, you know, those sort of things. But as it was in wartime of course it brought people out. It gave them a little – it enlivened their lives as it were, you know. But no, it was quite something.

Was it a brass band playing?

No, it was a proper dance band.

Have you any idea who paid for it?

No, I haven’t got a clue. Never thought about it. I can’t even remember the frequency. It might have been… I can’t remember the frequency but I know… it might have been once a month or whatever.

Did people have to pay or not?

No, just walked in the park.

Did they dress up for it?

No, I think they just turned up. Just turned up and people danced… you know, fine. No problem. Mind you I wasn’t of the age to think about fashion or whether they had their best suits on or not. But no, people just turned up.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Ann Foster watches the band for nothing

We never had money to go into the sweet shops and that because Mum couldn’t afford it because she was on her own. The real treat we had, on the Friday night, was the bandstand in Maryon Park. It was a really big bandstand and every Friday night they would have the different musicals and people on the stage. There would be the fold-up chairs. If you wanted to sit down you went through this little gate and it was a few pence to sit down but we never sat down. We’d stand outside because we could still see it all. We used to be allowed one packet of crisps each and that was it. I used to crush mine to pieces so that they would last the whole time. My sister, she would say something about it because she used to just eat hers quickly.

Mum said where the old shed was there was a soldier had murdered his girlfriend during the war, when he came back. The shed had four sides so we were allowed to sit on the front side that would face the bandstand but we weren’t allowed on the sides or the back of it because the back of the shed faced up to the top lawn and there could be people looking at us through the trees. So we used to sit in the front and that would be absolutely fine to sit there.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Connie Raper remembers the Bandstand after the War

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

You said you went to Maryon Park. That was when the bandstand was there, is that right?

That was after the War that was.

Was it?

The bandstand. I can’t remember it being there before the War because we were only children, only little children then, but when the war had finished I’d got my John… we used to go up this little park on a Sunday and there used to be a bandstand there and we used to dance, ballroom dancing round the bandstand. It used to be lovely.

And did someone call out the different dances that you were doing?

I daresay they did but I can’t remember that.

Were there lots of people there dancing?

Oh, yeah. My husband’s nephew and his wife – they were champion dancers. They were really beautiful. Harry Fenning… They were really beautiful dancers and we all used to watch them, you know, when we got the chance but we used to love it. It was lovely up there.

Who played the music?

Some band of some sort. I don’t know if it was the RA band or not. I don’t remember.

Audio Extract: Connie Raper remembers the Bandstand

Children playing

Extract from Interview Transcript: Connie Raper remembers the ‘swing park’

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.) What else was in Maryon Park at that time?There used to be the… in one of the parks there used to be swings.

Was that the one where you go over a railway bridge to get to the swings?

Yeah, that’s the swing park. What we use to call the swing park. When we were children we used to go in the swings and all that. It was lovely but, as we got older… the boys were in one playground and the girls were in another playground… but as we got older they put the two playgrounds more or less together, you know. In that one they built tennis courts because there was a lot of tennis played up there then.

Did the swings… did they have a supervisor there?

Oh, yeah. Very strict supervisor in the swings. She was a very nice person but she was very, very strict. You weren’t allowed to go too high on the swings. And the boys used to stand on the swings and go, you know, and she used to be out after them. “Get down, get down. No standing on the swings.” Oh, yes. It was lovely.

Did she have like a little hut there?

Oh, no. She had a nice little room. The girls’ playground was down there and the boys’ playground was up higher. She had her little room on the boys’ playground so us girls used to have to walk up about five steps to get to her.

Yes, I think I remember that now. It was near… overlooked the railway line, didn’t it?

Yeah. Yes, it was lovely.

Did she wear a uniform or was she just ordinarily dressed?

I don’t really remember but I can’t remember a uniform. Park keepers used to wear uniform but I can’t remember if she did. I can’t really remember but all I know is that she was very, very strict. She had to be because the boys were like bullies.

Well, they get excited, don’t they?

Audio Extract: Connie Raper remembers the swing park

Extract from Interview Transcript: Rose Savinson remembers the swing park

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

I don’t know that they did play that much unaccompanied. I think I was there most of the time but, certainly, we used to use the bottom park, Maryon Park, most because it was right by the house and my earliest memories are the swing park, and it was a bit different then. It had big swings and little swings. It had an area that was designed for small children, which was separated from the older ones. We used to go down there a lot and then, obviously, there was things like the railway line and sitting and looking over and waiting for the trains to come past. And the trains used to do all hoot as they went past. That’s where they did things like learn to ride their first bikes and it was ideal because you’d got that big sort of expanse of green where the tennis courts are and a huge path that goes all the way round so that I could watch them from afar and they could take off on their bikes and do the circuit. So that was really great. They were there a lot.

Audio Extract: Rose Savinson remembers the swing park

Audio Extract: Joan Harbottle remembers the swing park

Audio Extract: Ann Bedwell remembers the ‘swing park’

Audio Extract: Ron Roffey recalls the play area in Maryon Park

Extract from Interview Transcript: Paul Stephens remembers the cinema van

The cinema lorry – or van – it used to come into Maryon Park every summer, in the fifties, early sixties and show films. Just near the tennis courts and near the café in Maryon Park and they used to put chairs out and seats for the mothers and fathers and the children. Of course, the children used to sit in front. So it was great fun watching films, funny films and Disney films, licking a lollipop and playing with your friends. That was a great memory of mobile cinemas then.

Was that a form of van where the screen was in the back of the van or was this a separate screen?

I can’t remember actually. I think it was a separate screen but I’m not too sure. It’s going back to when I was about nine. It’s 1959 or so.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Rose Savinson talks about living next to Maryon Park

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

I suppose the parks became more prominent in my life after I had children. I had my first child in 1981. At that time we were living over in Victoria Way, which is a little bit further over the other side of Charlton and I was aware of the parks… definitely… and aware of the animal park, most certainly. Used to wheel her in her pushchair over to the animal park quite a lot. But then it got better, really, when in 1982 we moved over to Maryon Road and we actually lived in a house that was just four doors away from the entrance to the bottom park… to Maryon Park. I think as soon as I walked in there it was like a little oasis. It was so calm, it was so quiet, so beautiful. So remote you really could feel that you weren’t in London at all. We used to have a very wild back garden that sort of went up a hill onto a ridge overlooking the park, which was absolutely fabulous. We used to hear things like… there used to be a cuckoo regularly. We got a regular cuckoo that came in the spring. I remember, once, our daughter waking us up at four in the morning saying, “Mummy, daddy… mummy, daddy, I can hear the cuckoo.” We were really pleased that she was listening for cuckoos but it was rather early.

Once we moved there I sort of felt a bit of ownership with that park. I was in there every day, every day with the kids and I just sort of felt somehow it was sort of… not that it was mine exactly but I was part of that whole place. I felt like it was an extension of my house, an extension of my garden being in that park.

Audio Extract: Rose Savinson talks about living next to Maryon Park

Park Wardens

Extract from Interview Transcript: Ann Foster remembers Mrs Broom

I can remember the park mainly because we spent most of the time in the swing park, where Mrs. Broom was the lady who sat in the hut with her little cooker and she sat there all day – obviously, not every day but there would be somebody else that would take over – but, over the years that we were children, she always seemed to be there. She was very kind and we used to do things, obviously, we weren’t supposed to like making the slide greasy with candle wax so that it went faster… and it was a very, very high slide. When I think now I don’t know how we did it.

I know one day, when we was in the swing park, we found sixpence under the park bench so we gave it to Mrs. Broom. ‘Here’s a sixpence,’ because we’d been told if you handed anything in and it didn’t get claimed we’d get it back. It was me and my friend Sheila Land. So we handed it in and she gave it to the park-keeper when he came round and then we kept saying to him, “We will get that money back if no-one collects it?” And we did get this sixpence back, so we had threepence each.

Maryon Park, Keeper’s Lodge. Built 1896

Charlton Tunnels

A web site “subterraneangreenwich.blogspot.co.uk” in 2010 posed the question what happens if the cave discovered in 1894 were to collapse!

“Discovery of a Cave in Hanging Wood. – During the operations of the workmen on the North Kent line of the South Eastern railway when tunneling under the hanging woods, at Charlton, near Woolwich, they came upon a cave of considerable dimensions, cut in the chalk and flint rocks. A great quantity of sand has fallen at one end, blocking up the side from which it has apparently been entered, and the workmen are now busily employed in shoring up part of the roof of one of the chambers, the railway passing over ts entire breadth. Four chambers have been discovered, forming alternate recesses, from the main cave leading in a westerly direction. The roof of the cave is on a level with the line of the railway, and the base 12 to 14 feet lower. The atmosphere in it is remarkably dry and pure, and presents a great contrast with the damp and close atmosphere experienced in passing along the tunnel to the extremity where the cave has been discovered. The men state they found a knife and a spoon on exploring it, and they turned their discovery to good account on Sunday, having lighted the whole of the tunnel with candles, and conducted visitors over the cave at the extremity, charging them 3d. for admission.” Kentish Mercury, Saturday March 24 1849.

To complete the railway line, two railway tunnels were constructed to pass under Hanging Wood, one 150 yards in length, the other 100 yards, lined with bricks manufactured by William Dawson of Plumstead. It is not now known in which of the two railway tunnels the other historic tunnels were discovered. Royal Borough of Greenwich, Parks Department Management Plan. 2008

Gilbert’s Pit

Gilberts Pit, a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

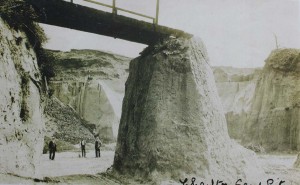

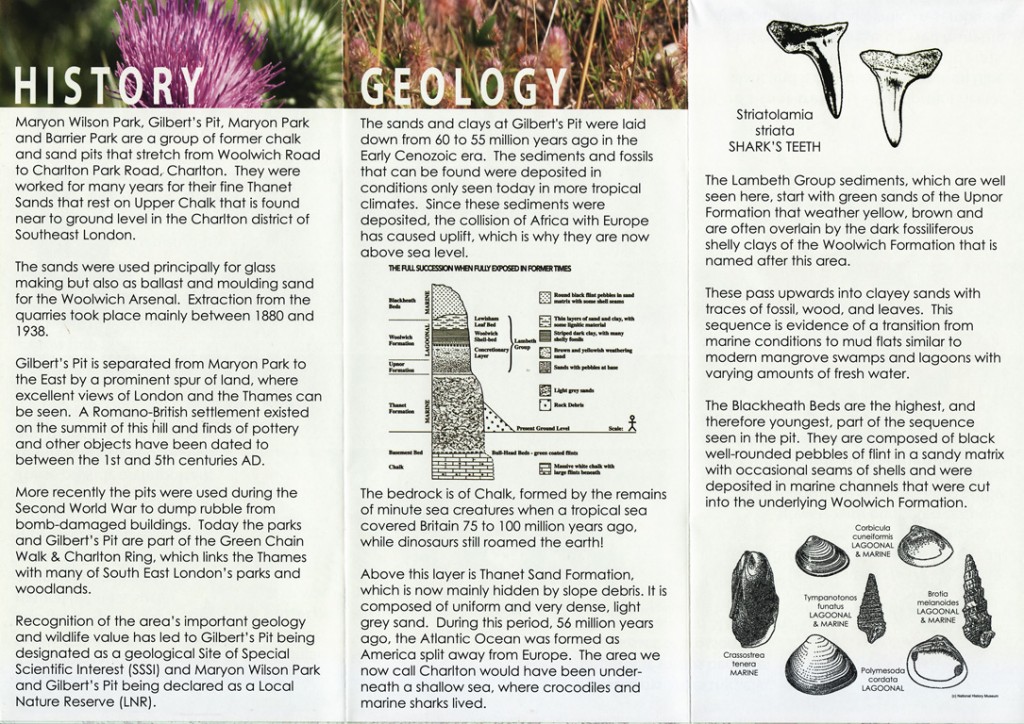

Gilbert’s Pit was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) first notified in 1953, revised in 1975 and Notified, under the 1981 Act, in 1985. The site covers a disused pit cut into a sequence of Lower Tertiary sediments dating from approximately 55 million years ago. Faces are present on the southern and eastern sides rising to over 20 meters above the floor of the pit.

The series of layers can be seen on the faces showing a sequence starting with Chalk, overlaying Thanet Sands and Woolwich Beds and capped by Oldhaven (Blackheath) Beds on the highest parts. Some of the beds are important for their fossils of plant, sponge, mollusk, fish and reptile remains. The pit is now overgrown with primary and secondary succession woodland species, along with woody weeds such as sycamore, which in places completely obscure the walls of the pit from view.

English Nature funded the installation of a palisade fence surrounding the central ridge, hoping to stop the anthropogenic erosion. The S S S I area extends into Maryon Park in some places, but the main feature of interest is the central ridge that runs between the Gilbert’s Pit and Maryon Park.

History The area known as Gilbert’s Pit was originally part of the ancient Hanging Wood. The dramatic topography that was present on the original ridge-line (now almost completely changed) was created largely by anthropogenic activity probably dating back to the early Iron Age. The earthworks constructed at that time are believed to have provided the original site of the Charlton settlement.

Excavations and surveys carried out since 1780 culminated in 1915 when F. C. Elliston Erwood, FSA carried out an extensive excavation and survey. His report, published as The Earthworks at Charlton, London SE7, concluded

“Charlton was a native settlement during the first half of the Roman occupation.”

The settlement is described as a large polygonal earthwork of probable pre-Roman age, with little evidence of occupation prior to the first century AD. The inhabitants were hut dwellers, but there was additional evidence of light timber frame and daub buildings with tiled roofs. Artifacts of contemporary industrial technology were also found; flint chips, flakes, rough scrapers, bones, furnace bars, querns, loom weights, nails, various bronze objects and two coins (from the reign of Claudius I, 41-45 AD). The bulk of the objects found unearthed date from 60-350 AD; the Bronze Age fragments found were the only ones discovered in the district. The finds are now displayed at the Greenwich Heritage Centre.

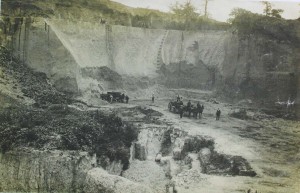

As part of the manorial grounds held by the Maryon-Wilson family from 1767, the sandpits were being worked from late 18th century until 1889, managed by Mr E. Gilbert, fueled by the industrial revolution.

The most notable of the Maryon-Wilson family to commercially operate the excavations was Sir Thomas Maryon-Wilson (1800-1869). Sir Thomas also held manorial rights over a large part of Hampstead Heath, and in addition to Gilberts Pit, conducted large scale commercial sand excavations in a pit on the West Heath section of Hampstead Heath, as well as his attempts to bar public access to, and develop large sections of the Heath.

The attraction of the site to industry was largely due to the abundant reserves of sand, chalk and gravel of the exposed Tertiary series. The Thanet sand was in great demand for processes including casting and moulding of brass and Iron, making glass and was also used as floor surfacing on parlour floors before carpets became widely available.

In 1889, Sir Spencer Maryon-Wilson presented an area of the worked out mineral pits to the LCC, which later became Maryon Park. Gilberts Pit; the remainder of the sandpits, was purchased by the LCC in 1930. It is separated from Maryon Park by a prominent ridge at the northern end of which are the remnants of home guard trenches which were used during the Second World War as lookout posts.

In 1985, Gilberts Pit was designated as a site of Special Scientific Interest notified by the Nature Conservancy Council under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 for the geological interest of the site. Charlton sandpit exhibits one of the most complete sequences of Lower Tertiary, Palaeocene rocks in the world, including the type section of the Woolwich Beds. Exposed in the south-western face of the pit are the Blackheath, Woolwich and Thanet Beds deposited approximately 50-55 million years ago. The sequence of sands and clays exposed in the pit have been the subject of much detailed scientific research providing vital information about the environment, climate, and geography that existed in Southern England during the Lower Tertiary.

Charlton Sandpit has also been classified by the London Ecology Unit as a site of Borough Grade 1 importance for Nature Conservation. Even though only a small fragment of the ancient Hanging Wood survives at the southernmost tip of the site, the site supports a good range of habitats and a particularly diverse collection of plant and animal species for an inner London site.

The site is included in the Green Chain Walk, but is not a public right of way.

In 1997, a 2 meter high security fence was erected around parts of the site including dangerous areas as well as a footpath system. In 1989, the London Wildlife Trust erected a security fence around the ecology area. There is an ongoing problem of continual erosion of the geologically valuable features as well as the nature conservation features of the site. Notes taken from the Parks department Management Plan, Royal Borough of Greenwich.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Frances Ward remembers Gilbert’s Pit in the 1980s.

(An edited audio version version of this extract may also be heard below)

I have fond memories. When Rachel was little about six, seven or eight we used to have a day out. We’d take the bus to Charlton Village, walk down through the parks, go to the animal farm, have a picnic, do the things you do – and the highlight was to end up at the cliff face at the bottom, overlooking the river, looking for fossils. Today you are not allowed as it is an SSSI. But 30 years ago we took spoons and a sieve and just dug out stuff, all kinds of things, mostly shells, shark’s teeth – a really special celebration – a lovely memory we have. At that time the tennis courts were not exactly derelict but open, you just walked in. If I had the energy we brought tennis racquets and stuff, I would play Rachel or she had a friend and they would play a game – it was a day out. Sounds silly for someone living in Lewisham to have a day out in Charlton but it was exactly that – a day out.

Yes we always took a picnic and got the bus back along the lower road, do a circle to Lewisham. If M& S was open would buy doughnuts and take them home. That was the climax- doughnuts for tea. I do have very fond memories of those parks, very fond memories indeed.

More recently, my husband and I do a lot of bird watching there. The bird life is fantastic, amazing. We’ve seen all 3 woodpeckers there, green, greater-spotted and lesser-spotted plus all the nice woodland birds, long-tailed tits, finches, all that kind of thing. So still take picnic because we like it. It’s become a day out.

Do you know if Gilbert’s Pit was more attached to Maryon Park than it is now?

It seem to have been always commercially mined from – not sure of dates – beginning of the nineteenth century, mined for sand, important in the growth of London – extension for the building of London’s suburbs. Local source of sand like living on a gold mine. That’s what Gilbert’s Pit is all about – commercial land. It’s part of the Manor, so the Maryon Wilson family would have had a financial interest from a very early date. Wouldn’t do the running themselves, too grand – would lease it out, or let it out.

We know it as Gilbert’s Pit – at different times it was mined by different people. One of the many pits in the area – more over in Plumstead. Aah, sand! Yes – money! And people went for it. Taken up on the river to wherever it was being sold. I find it surprising because if you think about it, it’s quite a long trek from here to the river, not 5 minutes. We have got pictures here of the little trolley things coming down from the pit being loaded into much bigger trolleys and pulled by horses down to the river on little railways lines. I think that’s where the profit lay – although a long way from the river sand was valuable to the building trade, worth making that effort, laying the railway line.

It was very fine sand.

Years ago , I read, in earlier days, it was used to sand floors – before carpets, stone floors, sprinkle on floor and bush it up and that took up all the grease. Charlton sand was used for that.

Audio Extract: Frances Ward on Gilbert’s Pit

Extract from Interview Transcript: Linda Walker remembers how dangerous it used to be.

My son, when he was doing his A levels, did a study on Gilbert’s Pit. Did a whole piece on Gilbert’s Pit for his A levels.

Was he allowed in?

He was doing this study, he was at Kidbrooke School and they allowed him in to Gilbert’s Pit. Most people couldn’t get in unless they went in illegally which a lot of people did – I have to say, it was dangerous. If you had children you didn’t encourage them to go there. Yea, he was allowed to go there and for a study of Gilbert’s Pit.

When you say a lot of people went illegally, did people tell you that or did you do it?

I did it once to see what it was like. I then realised that it was dodgy and if you fell somewhere – it was quite steep. By that time I had children, it wasn’t somewhere you went and wanted to encourage your children to play in. I know that children played in there, it was an exciting place to be – not a park that was prepared, much more dangerous and interesting, loads of local children used to go in there.

Extract from Interview transcript: David Sneeth digs for ammonites.

The sand pit up top, hop over the fence – those days no grass, clear sand… all you gotta do is dig into the slope, the ammonites are all there, no other fossils. Bottom of the hill was a mine cart track and rusty old mine cart – ammonites all over the place!

Extract from interview transcript: Ron Roffey describes the dangers of Gilbert’s Pit

Gilbert’s Pit was over the other side that ran behind Pound Park Road and up Charlton Lane. Of course, that was great because we used to not only play football but we used to dig… make camps in there and dig into the side of the hill. When I think about Health and Safety now, I mean some of these things just fell in because the sand was so fine. You know, there was the danger of being… but it never occurred to us! We just dug into the side of the hill and made a little camp in there.

Extract from interview transcript: Bob Harris recalls the debates about Gilbert’s Pit

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

Well in 1990 I put myself up for election for the local council and, as such, had a passion and a commitment to culture (and the word culture in its broadest sense) and became the chair of Leisure Services and, of course, the parks – that’s where the parks were administrated and sort of looked after and very much the place where the public could interface with the council – so, if you like, it became a much more important function of my thinking.

I spent a lot of time thinking about parks. I absolutely remember the debate about Gilbert’s Pit, when (quite rightly) the council was challenged by the appropriate bodies for really not defending Gilbert’s Pit as a site of scientific interest and there was some very interesting and challenging thinking around that because, on the one hand, the sort of scientific authorities wanted us to fence it in and turn it into a completely ‘no-go’ area for anybody but the accredited, but that kind of spoilt the daily fun of a lot of young kids who spent their time, you know, climbing around the old quarry.

It really was one of the most interesting debates we had at council because, in a sense, it wasn’t a political story but it was one of these conundrums of how on the one hand do you preserve something that’s very special for the whole community, you know, but also enable it still to be a practical, living useable space. I never really worked out whether we got it right but, in the main, I think eventually it became a bit of a truce really. I mean, the fences went up but I think most of the kids got through the fences and got to play in the park.

Audio Extract: Bob Harris remembers the debate about Gilbert’s Pit

Views from ‘Gilbert’s Seat’

Extract from interview transcript: Chris Hennings remembers working in the tea shop

I was born in Charlton so I know the parks very well. I used to go to Maryon Park an awful lot. It was only a short walk from home. We used to play in the swing park all the time. It wasn’t like now. It was very dangerous with concrete floors and there was lots of bumps and grazes. There was only a few things to play on but we seemed to manage to spend most of our day there. There was a little house in the park. There was a lady living there who happened to be my cousin’s mother-in-law so she was always good. We could always manage to get a drink from her or a plaster when one of us fell over once again.

As I got older I carried on and we used to play tennis in the park and things. And then – I’m not sure whether it was 1963 or ’64 – my friend had a job in the little cafe that was built, which was quite new, in the park. She went on holiday. Anyway, I took over her job and, at that time, they were building the Morris Walk Estate so I used to be very, very busy of a morning making bacon sandwiches and rolls for all the workmen that used to come in and great, big mugs of tea. It was quite exciting, especially for me who was quite young.

A teenage girl with all those young chaps?

A teenage girl with all the young… lot of Irish blarney coming out. In the afternoons it always used to be mums. You know, bring their children in, make them, you know, ice-creams and things.

Irish, they were Irish. That’s what we called them then, was it? Irish navvies. But no mainly it was young… you know, sort of mums and bringing their children in. I expect we sold a few sweets. Kids used to come in and spend their pennies and that. Probably a few of the elderly residents. I know we used to have lots of regulars in there. But I can remember it being a very, very happy summer. I just used to love working in there and I feel very sad when I go by there now.