Lower Charlton seen from Cox’s Mount, 1900. Holbern College (ex Charlton school) can be seen to the right with Siemens factory lying along the river where the Thames Barrier Gardens are today. The three storey building on the left is The Thames Barrier Arms, now a vets practice.

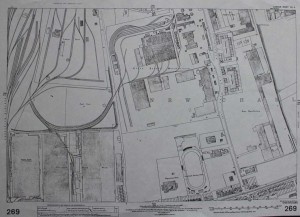

Area of Interest

A Unique Site at Charlton, by Barbara Ludlow

For hundreds of years, chalk was dug at Greenwich, Charlton, and Woolwich to be burnt in lime kilns. There were many kilns on the lower slopes of Blackheath Hill and until the beginning of the nineteenth century Greenwich South Street was known as Limekiln Lane. Two other notable sites were Charlton Church Lane and the part of Woolwich, which was later to become Frances Street.

Nichols’s Lime Kilns, later the Crown Fuel Company and Greenwich Pottery Lime was essential to the brick and tile making industries. It was also used when making mortar and manure. However, when Thomas Nichols left Dartmouth, Devon to settle in New Charlton in the late 1840s much of the local chalk was built over or worked out. Even so he established himself as a carpenter and lime merchant in Hardens Manorway. Nichols’ business prospered and in the mid-1860s, he moved to a site between the North Kent Railway line and Woolwich Road. Here, on the eastern side of Charlton Church Lane and close to the fairly new Charlton Station he concentrated on lime burning. Thomas moved his family into 444 Woolwich Road, promptly named the house ‘Lime Villa’ and had two Staffordshire style bottle kilns built. The Business could not rely on local quarries so he brought in limestone from Riddlesdown Quarry, near Whyteleafe in Surrey. The 1871 Census shows Nichols employed thirteen men and that they also lived close to the works.

Eventually the business passed to Fred Nichols, and in the early 1920s, the then owner Eric Nichols sold the premises. Lime burning was finished in Charlton but the buildings and bottle kilns, with a chalk capital ‘N’ set in the neck of both, were purchased by the Crown Fuel Company to produce heating elements for gas fires. In 1950, the Festival of Britain seems to have inspired the Company to branch out into pottery and use the kilns for making decorated ware and small figures of animals, mostly dogs. These goods marked Greenwich Pottery were for export only but they were advertised in the 1951 Greenwich Festival Guide.

Towards the end of the 1950s production ceased but a bottle kiln of c1868 and buildings of about the same date were left. Everything was demolished in 1965 and Barney Close, Charlton, was built over the site. Before the buildings were demolished an Industrial Archaeologist surveyed the site and a photograph of c1872 was discovered. Nichols is seated and behind him stand five of his workers. A photograph was taken of the attractive mid-Victorian bottle kiln before it was demolished. Greenwich Industrial History Newsletter, May 2001, Vol 4 Issue.

Some Industries of Charlton: Diana Rimel BA, Local Historian.

Charlton had a lime burning industry from the 17th century and kilns in the 1860s. Maryon Wilson Park and Charlton Athletic football club were the sites of chalk pits and are now mostly filled in.

After the Great Fire of London (1666) chalk was used for the rebuilding of the City. Chalk from the Charlton pits was also taken to fertilize the Essex flats and support its agriculture.

Sand pits were also excavated here on estates owned by the Roupell and Boyd families. These pits from 1914 became the site of ‘The Valley’, Charlton’s Football Ground. Lewis Glenton, a sand and gravel haulier, built a railway named after him to remove both, completed in 1841, signs of which were visible until relatively recently. Chalk and sand were excavated and transported to the Thames until early in the 20th century. The railway was then used by British Ropes Factory Ltd. which had a factory in Anchor and Hope Lane, and had the right to use the railway for transport of flax and hemp from the river wharf to their factory.

Sand and gravel are basic raw materials for glass making.

The glass industry is known to have been in the Greenwich area from Tudor times. Sand in Charlton pits was used for making glass ornaments and bottles. More & Nettlefold Ltd began their glass works in Anchor & Hope Lane in 1907. And up till about 1930 United Glass Bottle used sand from Charlton pits.

This firm incorporated many other glass manufacturing businesses of some age. The Charlton factory employed over 2000 people and had a plant in St Helens. In its heyday it was the largest company of its time in Europe and produced over 300 million glass containers. From 1919/20 the Charlton plant specialised in the installation of Owens bottle making machines, as well as producing medical, milk, jams and pickle bottles, etc.

Of the many companies that produced electrical parts and cables Siemens is one of the best known. Halske Co. Cable manufacturers and electric telegraph contractors, set up in 1847. They became the British branch of the German firm of Siemens, and cheap riverside land on the banks of the Thames at Charlton Pier became available in 1864. William Siemens already had premises in Millbank and needed to expand. He had become the leader in scientific and engineering fields in this country since 1844. The location of the Charlton land subsequently enabled submarine cables to be easily loaded onto ships moored there, and in 1875 2,565 miles of cable to cross the Atlantic were supplied by the firm. The works also produced all kinds of telegraphy instruments, apparatus, materials and new inventions, which resulted in a huge expansion.

By 1909 Siemens works covered 15 acres, employing 1,300 people. The site had cable, railway signalling and instrument shops, plus those for manufacturing cable insulated with gutta percha, pattern making and joinery, electrical accessories, stores, paper and saw mills. Expansion continued and the two World Wars gave Siemens much work. In the Second World War Siemens also worked with Johnson and Phillips, another well known Charlton industry, to produce PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) 35 miles long, weighing 2000 tons and laid under the Channel to supply fuel to the Allies. In the 1950s and 60s after mergers and closures the firm closed. The site became part of the Westminster and Mellish Industrial Estates.

Walter Claude Johnson and Samuel Edmund Phillips formed their partnership in 1875. (From 1964 the firm became Delta-Enfield Cables). They had factories in New Cross and Charlton (Victoria Way), and were responsible for many projects (most notably PLUTO). They made a major contribution to cable manufacture, laying and telegraph construction world-wide. They described themselves as Telegraph Engineers and Electricians, and pioneered much new technology, including insulated cables for cable carrying and providing electric power for factories and homes. The Works at Charlton Way were demolished in the late 1980s.