Area of Interest

Chronology of Charlton Parks Estate

Maryon – Wilson Family Tree

Maryon-Wilson Family

Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon Wilson, 11th Bt.

Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon Wilson, 11th Bt. was born on 19th July 1859. He died on 12th May 1944 at age 84.

He gained the title of 11th Baronet Wilson on January 1st 1898.

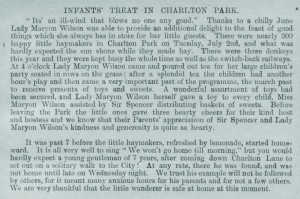

“In April 1898, to honour his succession to the title he chose as his first duty in Charlton to open a new gymnasium...for the children in Maryon Park.

Sir Spencer was best known for his love of outdoor sports. Apart from the fives court, Charlton House grounds also boasted four tennis courts, two croquet lawns and polo field. he was often seen in the neighbourhood seated on his favourite speckled pony, and it was due to his generosity that many a horse trough owes its existence. The one at the top of Church Lane was presented by Sir Spencer at the time of King Edward V11’s Coronation. Local inhabitants also subscribed and contributed the drinking fountain. Another trough presented by Sir Spencer graces the entrance to the Warren Golf Club at very Hill.” John Smith, 1970.

Lady Minnie Elisabeth Maryon-Wilson

Lady Minnie Elisabeth Maryon-Wilson was born Minnie Elisbeth Thornhill on 22 May 1863 at Hyderbad, Deccan, India. Sir Spencer Maryon-Wilson and Minnie Thornhill were married on 29 October 1887 at All Saints, Ascot Heath, Berkshire. She died at Inverness, Scotland on 13th April 1947. “A stained glass window in the south aisle of St. Lukes Church, by the Wilson private pew – representing St. Luke with St. Margaret – was presented by Viscountess Gough, above two stone tablets in memory of her parents.” –John Smith, 1970.

Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson

Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson was born on 14th March 1902. She died on 9 Mar 1977.

Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson was the daughter of Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon-Wilson and Lady Minnie Elisabeth Maryon-Wilson. She married Hugh William Gough, 4th Viscount Gough of Goojerat, son of Hugh Gough, 3rd Viscount Gough of Goojerat and Lady Georgiana Frances Henrietta Pakenham, on 12 November 1935. She died on 9 March 1977.

As a result of her marriage, Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson was styled as Viscountess Gough of Goojerat on 12 November 1935. From 12 November 1935, her married name became Gough.

Hugh William Gough, 4th Viscount Gough of Goojerat

Hugh William Gough, 4th Viscount Gough of Goojerat was born on 22 February 1892. He was the son of Hugh Gough, 3rd Viscount Gough of Goojerat and Lady Georgiana Frances Henrietta Pakenham, on 12 November 1935, 3rd Viscount Gough of Goojerat and Lady Georgiana Frances Henrietta Pakenham. He married Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson, daughter of Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon-Wilson and, on 12 November 1935. He died on 4 December 1951 at age 59.

He was educated at Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire, England. He graduated from New College, Oxford University, Oxford, England in 1913 with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.). He fought in the First World War, where he was mentioned in despatches twice and was wounded. He was decorated with the award of Military Cross (M.C.). He succeeded to the title of 4th Baronet Gough, of Synone and Drangan, co.Tipperary [U.K., 1842] on 14 October 1919. He succeeded to the title of 4th Baron Gough of Chin Kang Foo, in China and of Maharajpore and the Sutlej in the East Indies [U.K., 1846] on 14 October 1919. He succeeded to the title of 4th Viscount Gough of Goojerat, in the Punjab and of the city of Limerick [U.K., 1849] on 14 October 1919. He gained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in 1922 in the service of the 1st Regiment, Iraqi Cavalry. He gained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel between 1930 and 1934 in the service of the 1st Battalion, Irish Guards. He held the office of Justice of the Peace (J.P.) for County Galway. He held the office of Deputy Lieutenant (D.L.) of County Galway. He held the office of Deputy Lieutenant (D.L.) of Inverness-shire.

Shane Hugh Maryon Gough, 5th Viscount Gough of Goojerat

Shane Hugh Maryon Gough, 5th Viscount Gough of Goojerat was born on 26 August 1941. He is the son of Hugh William Gough, 4th Viscount Gough of Goojerat and Margaretta Elizabeth Maryon-Wilson.

He was educated at Abberly Hall, Worcestershire, England. He gained the title of 5th Viscount Gough of Goojerat, in the Punjab and of the city of Limerick [U.K., 1849] on 4 December 1951. He succeeded to the title of 5th Baron Gough of Chin Kang Foo, in China and of Maharajpore and the Sutlej in the East Indies [U.K., 1846] on 4 December 1951. He succeeded to the title of 5th Baronet Gough, of Synone and Drangan, co.Tipperary [U.K., 1842] on 4 December 1951. He was educated at Winchester College, Winchester, Hampshire, England. He gained the rank of Lieutenant between 1962 and 1967 in the service of the Irish Guards. He was admitted to Royal Company of Archers. He was member of the Executive Committee of the Standing Council of the Baronetage. He was invested as a Fellow, Royal Geographical Society (F.R.G.S.).

“In 1964 he (Lord Gough) became life tenant of the family trusts which included all remaining parcels of land and property (managed by the estate agents Farebrother Ellis & CO. Ltd.) and the Patronage of the Living at Charlton…… He is extremely interested in the affairs and present developments occurring in Charlton and actively supports the Charlton Society, its first President.” John Smith, 1970.

Maryon-Wilson Family use

Some thoughts from Lord Gough

“I believe my grandmother never liked Charlton and hardly went there after WWI.

In 1925 my late uncle who died of peritonitis in1937, who was then married, persuaded my grandfather to sell the big House and its contents to release some money for him. I believe that he has some of the income of the Charlton Estate as it was part of my grandparents Marriage Settlement. At any rate my mother’s expectations got much better on his death. He was at least 13 years older than my mother.

I think my grandfather kept control of the Patronage of the Living of Old Charlton consults his nephew the next Baronet and my mother. He had laid the Foundation of the Assembly Rooms in his younger days .

Kinveachy Gardens were named after the Estate he and his father rented near Aviemore in Scotland form 1885 to 1944.

My mother had fond memories of Charlton until 1915 where she and a group of girls had a Governess Miss Edwards who taught them well. She had to sell a considerable part of the Estate after World War 2 to pay duty and when it was very difficult to get materials to remedy Bomb damage. She certainly put up memorials to her parents in St Luke’s as well as the current Altar Table in memory of my father who died in 1951 and took much trouble in appointing the Rector taking advice from her first cousin. I have also found appointing the Rector very interesting as my mother had handed over interest in the Charlton Estate well before she died in 1977.

Before the First War my grandfather kept plenty of Coach horses as he enjoyed driving a coach and four and my grandmother was a keen gardener so a large amount of indoor and outdoor staff were employed. I believe that there was a small farm which supplied the big house.”

The Sale of Charlton House and Park

METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF GREENWICH

TOWN’S MEETING

CHARLTON HOUSE AND PARK

Notice is hereby given that Public

Meetings of the Residents of the

Borough of Greenwich will be held as follows.

SATURDAY 14th MARCH 1925 at 8pm

at the

VICTORIA HALL………………………………

The Kentish Mail: Woolwich, Friday March 13 1925. No: 4,267 – Vol. LXXXI

Charlton House: Town’s meetings Discuss Town Hall Scheme

…… Councillor Horne speaking as Chairman of the Social Committee dealing with the matter, said that a Town Hall for Greenwich had been under discussion for many years. The present Town Hall was purchased in 1876, and for some years past had been found very inadequate to meet the convenience and work of the Council and staff…..They also suffer from the noise of trains and trams.When the question was gone into in 1920, it was found that the expense of erection of a new building would be £120,000, but of the purchase price of Charlton estate, £13,000 was the amount attached to Charlton House. Those figures alone showed the economic basis of the proposal…..Those who took a pride in the historical record of the ancient borough….were anxious that this building would be turned to some account for the inhabitants of the borough.

Mr. E J Holland, a representative of the North-West Ward Labour Party said he opposed the shifting of Town Hall from Greenwich Road to the “aristocracy side” of Blackheath. The electors of the North-West Ward were going to be put to great inconvenience by the proposal. Charlton House was a very beautiful and interesting place and he was sorry that the council did not reveal the true history of how it was obtained. It was got very cheaply, but it cost a lot of money. He suggested that Charlton House should be a maternity home for the mothers of Greenwich.

Dr. Morgan..went on to say that it was curious how the Town Hall, which had proved satisfactory so far, and which was in a traffic centre, should suddenly be found to be inadequate and a proposal be brought forward to put it in a comparatively uninhabited section of Charlton. He wanted the present Town Hall laid open to the public for inspection, so they could see for themselves the condition under which the staff worked.” The Kentish Mercury, Friday 20th March 1925

John Smith in The History of Charlton states: “In June 1925, the Greenwich Borough after prolonged negotiations concluded the purchase of the house and park comprising some 108 acres for £60,000. About 43 acres of the park were later transferred to the London County Council to form a playing field and athletic track while some five acres around the house were preserved for the building. The remaining part of the land was developed as the Hornfair estate comprising both private and council houses….. The House was first intended for use as the Borough Town Hall but in March 1928, the ground floor rooms in the north wing together with the central hall were opened as a new branch library. The library later extended to the re-altered south wing and a museum showing prints of local interest and pottery and porcelain from a private collection occupied the remaining vacant rooms.”

Charlton Park and Shooters Hill

A letter from Mr. Basil Holmes, secretary to the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association submitted information regarding his association’s support of efforts being made to secure Charlton Park and grounds and further portions of Shooters Hill for the use of the public:………this proposal emanated some time ago from the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association, after the vendor had made a proposition that the association should acquire the mansion and some ten or twelve acres round it. To this the association replied in the negative, but said that it would be well worth while for the whole of the park, including the house, be preserved for the playing of games, and it thereupon asked the vendors to quote a price for which they would be prepared to sell the whole area for the purpose in view. After considerable negotiations the association has at length secured an option of purchase for £60,000. to hold good for a period of two months from the end of April. It at once laid the matter before the Greenwich Borough Council…..with a view to finding out to what extent that body would be prepared to assist in raising the money required, and it was the association to await a reply before communicating with the London County Council…however…the Borough Council itself approached the London county Council…………..Altogether it is a very fascinating scheme,……….it would prove a priceless asset for the physical and moral welfare of the younger people of the metropolis. The Kentish Mercury, May 30 1924

Sir Spencer and Tony Sykes by Tony Lord

” If I had a pound for every time I’ve passed Charlton House on my way to Woolwich, I’d be sunning myself on the terrace of a villa in the South of France with my yacht anchored in the bay.

Sir Spencer Pocklington Maryon-Wilson lived in some style at the old place with his family. Trees and shrubbery, high railings and walls surrounded the grounds, tended by six gardeners, while fourteen servants some of them dressed in blue and gold livery, were employed in the house. By some oversight our family living a stone’s throw away in Victoria Road were never invited to tea

Sir Spencer took a great interest in local affairs, riding about the district on his pony. The horse trough, still there at the top of Church Lane, was presented by him at the time of King Edward’s coronation. St. Luke’s church nearby benefited by the gift of gilded reredos (that’s an ornamental screen behind the altar, I didn’t know that either until I looked it up) and some Evensong candlesticks. During the Great War, Sir Spencer opened the grounds of the house for use as a camp with part of the house itself becoming an auxiliary hospital.

The family moved into the nursery wing but in 1916 an outbreak of typhus in the camp forced Lady Wilson and her young daughter to move temporarily to their house and estate near Rugby. ‘Temporarily’ became permanent and the family never returned to Charlton.

The rising cost of living and higher wages in 1919 compelled Sir Spencer to put the house and contents on the market. The pictures and valuable furniture were sold at auction but the house and grounds found no purchasers and years passed with the land becoming overgrown and Charlton House having an increasingly neglected and gloomy appearance.

Then in 1925, Greenwich Borough Council bought the lot for £60,000 intending to use the house as the town hall. This ideas was abandoned and eventually in 1928 it became a branch library and museum of sorts.

Sir Spencer lived on at his various residencies until in 1944 when he died in Scotland, aged eighty-three. he left an estimated estate valued at £730,000 plus 1200 acres of Scottish grouse moors.

At the end of the Second World War the borough Council purchased ‘Springfield’ from the Maryon – Wilson Estates. ‘Springfield’ was nine acres of grazing land across the road at the front of Charlton House. I remember as a boy, peering through the high spiked railings which surrounded the land, down the steep slope to the pond and natural spring at the bottom. A section of these railings still stand at the top of Church Lane.

The council had previously bought the freeholds of six large houses fronting Charlton Road. In 1948 work began demolishing these properties and preparing the site. This was difficult because of the steep sloping grassy banks and the bubbling water at the bottom. Eventually nine blocks of high flats were opened in 1951 – 2.

Two years before this, seventy year old Tom Sykes, a widower, had to be evicted from his timbered cottage on the land in the corner of ‘Springfield’ to make way for the flats. Tom, an ex-Policeman, had lived there for twenty-three years working his acre of land. Des Taylor tells me he kept pigs. Sir Spencer had told him when he moved in “The cottage is yours for life and I shall never turn you out”.

Each day Mr. Sykes watched the sinking of massive foundation piles draw dangerously near his home until, in April with a fifteen foot high mound of earth a few yards from his back door, Tom moved out to a requisitioned flat in Blackheath and the picturesque old cottage was flattened.

Progress sometimes comes at a price, I’m afraid.” Reproduced by kind permission of Tony Lord, written for publication in The Mercury 2011

Before the park was there

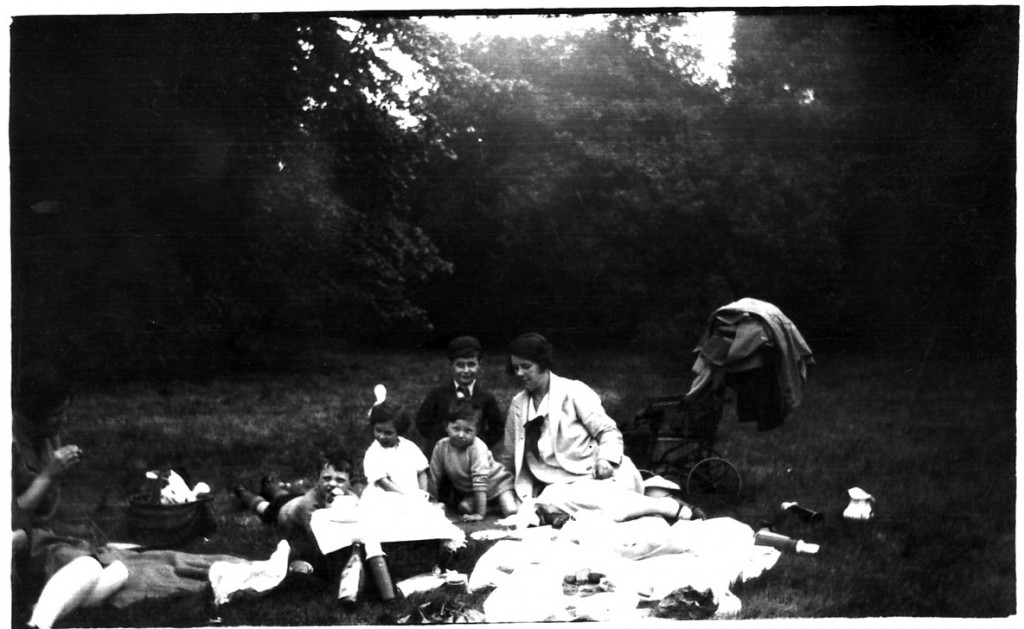

Picnic in Charlton House grounds, about 1930. From left to right: a Family friend, son of the man who wound the clock in Charlton House, Jean Humphries aged 5 years, Jim Humphries aged 9 years, Edward Denman aged 5 years, Mrs. Ida Denman wife of the watch maker, 19 The Village, Charlton. photo contributed by Miss Jean Humphries.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Jean Humphries remembers playing in Charlton House grounds

(An edited audio version of this extract may be heard below)

My first recollection of Charlton House grounds is when I must have been about seven or eight and we used to go for picnics in there only because my father was friendly with the man who wound the clocks. I was born in ’23 so it would have been about 1930, wouldn’t it? Thirties, early thirties. And he used to bring his family and our family. But it was very, very good for us because we went round to the back of the terrace and there was a great big chestnut tree on the right of the lawn which us children liked. I can remember going there but then, as I grew older, I used to go around there to play with other friends, when the park was open to the public.

This man Mr Denman was kept on to keep the big clock going in the tower. He had a watch-making and jewelery shop in Charlton Village opposite to where we lived. We came from the bicycle shop.

We went for conkers and we went up those rides… up towards Canberra Road… and then round and down again and, over in one corner, I know there was a squash court which intrigued us a bit but we couldn’t go in there then. That was fenced off but we used to look at it. It belonged to the Maryon Wilsons. lovely place to play in.

Audio : Jean Humphries remembers playing in Charlton House grounds

Extract from Interview Transcript: May Wellard on art at Charlton House.

Do you have any memories of Charlton House?

Yes , because it wasn’t open when we first moved there. It had a low, red brick wall surmounted by railings and a thick privet hedge all the way round right up to Marlborough Lane and you could see the statues still in the garden there. Eventually you were able to join the adjoining library. That was the first part.

It was a public library then. I can’t really remember the house being opened. We used it… I can’t remember even using it. I suppose I used it when it became a community centre, which was much, much, much later.

So you never went in it as a young person because it was just private?

I went into it… I should imagine in the early fifties because I remember they had some very attractive drawings… paintings, not paintings… sketches… all the way round the walls which, eventually, I think just disappeared.

An extract from ‘Old and New London by Edward Walford, 1878, Vol 6 pages 224 -236.

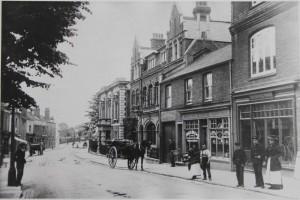

Passing along Charlton Road, which runs eastward from Vanbrugh Park, a short walk brings us to the pretty little village of that name, which stands on the high ground between Greenwich and Woolwich, and has a charming look-out over the valley of the Thames. Here we find ourselves upon the chalky soil of Kent; and although the place has within the last few years lost much of its rural character, through the gradual extension of buildings, it is still green and pleasant. In this neighbourhood, if we may believe the Gentleman’s Magazine, in 1734, a large eagle was captured, and, strange to say, by a tailor. Its wings, when expanded, were three yards eight inches in length. It was claimed by the lord of the manor, but was afterwards demanded by the king’s falconer as a royal bird, and carried off to Court. Its subsequent fate is not recorded.

In Philipott’s “Survey of Kent” (1659) we find that Charlton was “anciently written Ceorlton, that is, the town inhabited with honest, good, stout, and useful men, for tillage and countrye business;” the Saxon word ceorl signifying a husbandman, or churl, as it is termed in old English, whence Churlestown or Charlestown was easily derived, and so by abridgment Charlton.

The church, a red brick-built edifice, dedicated to St. Luke, has a lofty embattled tower, which serves as a landmark for those who sail up or down the river. It has a double roof, supported by pillars, forming arches down the centre of the building. The edifice was erected by the trustees of Sir Adam Newton, in 1630–40. The chancel was added by the rector in 1840; in it is a handsome stained-glass window. Among the monuments in this church is one for the Hon. Brigadier Michael Richards, Surveyor-General of the Ordnance, who died in 1721; he is represented by a life-size figure of a man in armour, holding a truncheon in his right hand, with military trophies, &c. A marble statue, by the younger Westmacott, commemorates Sir Thomas Hislop, G.C.B., who died in 1834; and there is also a monument to Sir William Congreve, the inventor of the rockets which bear his name: he died in 1814. A neat tablet by Chantrey records the interment in the vaults below of the Right Hon. Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister, who was assassinated by John Bellingham, in the lobby of the House of Commons, on the 11th of May, 1812. In the churchyard, close by the porch, lies buried Mr. Edward Drummond, who was shot in the neighbourhood of the Houses of Parliament, in January, 1843, in mistake for Sir Robert Peel, the then Prime Minister, whose private secretary he was. Here, too, is buried James Craggs, Postmaster-General, and father of Pope’s friend, Mr. Secretary Craggs, who, in consequence of the scandal occasioned by their connection with the South Sea Bubble, destroyed himself by poison in March, 1721; there is a monument to his memory in Westminster Abbey.

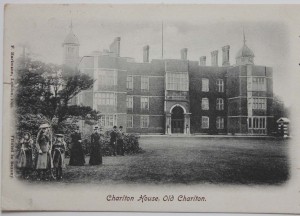

Immediately to the south of the church stands Charlton House, the seat of the lord of the manor, Sir Spencer Maryon-Wilson. The manor of Charlton was given by William the Conqueror to his half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, from whom it passed to Robert Bloet, Bishop of Lincoln, who, about the end of the eleventh century, gave it to the priory of St. Saviour’s, Bermondsey. Having reverted to the Crown at the Dissolution, it was given by James I. to one of his Northern followers, John, Earl of Mar, by whom it was sold in 1606 to Sir James Erskine, who, in turn, disposed of it in the following year to Sir Adam Newton, Dean of Durham, tutor to Henry, Prince of Wales. In 1659 it passed to Sir William Ducie, afterwards Viscount Downe, and subsequently it was owned successively by the Langhornes, Games, and Maryons, and also by Lady Spencer Wilson, from whom it has descended to the present owner. The mansion, which Evelyn describes as “a faire house built for Prince Henry,” is pleasantly situated in extensive park-like grounds; it was commenced by Sir Adam Newton in 1607, and completed in about five years. The house is very pleasantly situated on rising ground overlooking the Thames and the opposite shores of Essex, and commands a most delightful prospect, which has been described by Evelyn as “one of the most noble in the world for city, river, ships, meadows, hill, woods, and all other amenities”—a prospect, by the way, which has been considerably abridged of late years by the growth of the surrounding trees. Its situation might indeed well recall to memory those charming lines by Mrs. Hemans, descriptive of the halls of our old nobility:—

“The stately homes of England,

How beautiful they stand!

Amid their tall ancestral trees,

All o’er the pleasant land. British History Online.

The Library

Extract from Interview Transcript: Phyllis Flynn remembers the library in Charlton House

We used to like going into Charlton House – the Jacobean House built in 1607 (celebrated its 400th recently). They used to open it to the public every so often sometimes in the summer so we went in there a few times. We used to go in the library – don’t think they’ve got it there now, it’s not used as a library , it’s used as some scheme for little children. Used to go in there quite regularly to borrow books and have a look round and things like that. Opened certain mornings, days of the week – you could just go in there and borrow a book and generally look round.

Charlton House – not changed, same as it is now. Great big rooms upstairs – sort of house Henry VIII would have gone into – grand, no furniture or anything, decorations, old fire places – we used to like going in there and when we went in there we used to go in the Rose Garden, a garden to the back of Charlton House – one section of the garden you could go into, it’s not called the Rose Garden, called it something else – it’s still there. Me mother and I used to go in there quite frequently, quite a lot, used to enjoy sitting in there in the sunshine. Then we’d have a walk and somewhere else.

Audio Extract: Joan Harbottle describes the Library

Extract from Interview Transcript: Jean Humphreys remembers the Museum in the House

When the museum was first opened there was a bird… wild birds in there.

Where was the museum?

In the house. It was stuffed… all stuffed birds but it was quite a good collection if you liked that sort of thing and, of course, the Victorians did.

And when the building had been taken over by the local authority, they kept this in the house.

Yes, and you could go in up that nice staircase. That was something. Well it’s still good, isn’t it?

Yes.

I used to enjoy that. But these keepers… of course they weren’t really pleased to see a little mob of children and so they… I think we used to play them up rather. We weren’t very good children.

What did you do?

Well, I suppose we called out to them or we’d just… they would appear on the terrace to see that we were behaving ourselves and we would run and hide and they would, you know, come round just to see what we were up to but then we’d run somewhere else and eventually we would go away. Give them a bit more peace! But that was rather naughty.

So the bird collection was upstairs?

Yes, in the long gallery. I think it’s called the long gallery. It was then.

So you would go into the house to go and have a look at that?

Yes and that’s where obviously the keepers were required to see that children didn’t damage the place, which we could have done quite easily if left to our own devices. I think that’s my main memories of Charlton House grounds.

HornFayre

Market, and fair, commonly called Horn-fair

In the year 1268, there was a grant from the crown for a weekly market to be held at this place on Monday, and an annual fair, for three days, on the eve, the day, and morrow of the Trinity. Philipott, who wrote in 1659, speaks of the market as then not long since discontinued; “the fair,” says he, “is not disused, but kept yearly on St. Luke’s Day; and called Horn-fair, by reason of the great plenty of all sorts of winding horns and cups, and other vessels of horn there brought to be sold. ”

This fair, retaining the same name, still continues; it was formerly celebrated by a burlesque procession, which passed from Deptford, through Greenwich, to Charlton; each person wearing some ornament of horn upon his head. This procession has been discontinued since the year 1768: it is said, (by a vague and idle tradition,) to have owed its origin to a compulsive grant made by King John, or some other of our kings, when detected in an adventure of gallantry, being then resident at Eltham-palace.

The Fair originally granted for May/June ( presumably to ‘Christianise’ the period of pagan fertility celebrations) and moved to St Luke’s Day later to connect the waving about of horns to the Ox.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45480

“The weekly market as well as the fair, granted by Henry III have been long discontinued.

Instead of the latter, a fair called Hornfair, was held yearly on St. Luke’s Day, October 18th, at which time ram’s horns and all sorts of toys made of horn were sold.

It consisted of a notorious mob who, after a printed summons, dispersed through the neighbourhood, met at Cuckhold’s Point near Deptford ( page 16) and marched thence in procession through Deptford and Greenwich to Charlton with horns of various kinds upon their heads, and after walking thrice round the Church, held the fair on the green before Charlton House. Since 1825, when the green was attached to the grounds of the mansion, the fair was held in the ‘Fair Field’, at the east end of the village, where the road branches off to Woolwich. The assembly was infamous for rudeness and indecency, which led to its final suppression by order in Council, March 1872 (?).

A sermon is preached at Charlton Church on St. Luke’s Day (fair day), for which the clergyman receives 20 shillings.” Hasted’s History of Kent 1886, Page 127.

Audio Extract: Phyllis Flynn remembers the Horn Fair

Audio: Ken Timbers begins reading an extract from The Shop

Audio: Ken Timbers concludes reading an extract from The Shop

Morris Dancing

Extract from Interview Transcript: Douglas Adams remembers Morris Dancing at Charlton House

As a musician, who could play for most teams, I played for everyone. So, I have to say, that’s why my knowledge of which parks I played in is a bit sketchy. I just went where I was asked.

The only one I remember was – clear knowledge – is behind Charlton House, as part of the Horn Fair celebrations. Later lots of other groups thought it would be good to have Morris dancers along and, at the time [in the 70s], we were very community-oriented – as long as there was a good pub nearby and we could collect money as well! So we did a lot more of those events. That was it.

I was quite excited by the… I saw pictures of the revival of the Hornfair but because, by then, I had a band as well I didn’t have much spare time to get involved with things. I did go along and watch Hornfair years ago and not play for them, which was nice. And I persuaded Blackheath, when it was revived, to go along, but it had lost all of its, sort of, pizazz really, and it was not a big success and I think that revival might have died away now. I think the procession wasn’t allowed to go on the road anymore so it had to go on the pavement and around the front of Charlton House and then to the back. In that time – that’s the eighties – we danced with Blackheath Morris quite a lot at events, at Charlton House but very rarely. I mean, it was mainly Greenwich and Meridian who I played for.

Most of the time Hornfair did have another musician there. There are very good women musicians there which, at the time, we were trying to encourage because most womens teams have men musicians and we were trying to encourage the girls to get involved. That’s really my recollection. I used to enjoy Charlton House events. I remember going to play once at a Mauritian event, which was marvelous for the food and their music. I don’t know what they made of us. There was a Mauritian community had a…

So the name Hornfair and the time that it was set up, might that have been at the beginning when Horn Fair was revived in the seventies or was it at some point later?

I think they might have coincided and I can tell you there are people who were active at the time, who might know better. The most important one’s now called Cathy Elvin. But she was a great driving force behind a lot of these things and famously she was known as ‘Big Cath.’

I was always keen to show off that we were local people, doing local things that anyone could join in with and that was more of the ethos at the time. You know, that this isn’t as its portrayed so often – you’ve got to be very fit. It’s quite dangerous if you don’t practice. The sticks really hurt if they don’t meet

You mentioned earlier about the provision of a bar, so, presumably, Charlton House, having a bar of its own at the time, it would have been a…

Well, not just that. There were two pubs down the road because what was an ideal spot for us was a nice afternoon community event, within walking distance of a pub so that we could meet there, have a dance there, have a drink, have a social time… go and do the performance when the pub was shut.

Dancing on grass is quite hard.

So you weren’t dancing on the grass at Charlton?

If we could find a hard patch, which we did – there’s a patch at the top, before the slope I think, that we’d go on but the grass was always well looked after there. The lawn was fine. It’s when it’s sort of, you know, quite long grass.

I suddenly remembered about Charlton House. That there’s a steep, sort of, grassy slope with a flat piece at the top and it was slightly damp. We had to dance at the top there and people did slip and one chap did slip down the ramp and it was quite… fortunately not hurt… but it caused an amazing commotion. And somebody might remember that, the Morris man slipping down the slope and crashing into a stall at the bottom.

In Memorium: Douglas Adams died on 21st September 2012 following a recurrence of cancer. Originally from Devon, he arrived in Greenwich in the mid-1970s and then lived near the Blackheath Standard. His main interest outside work was English traditional music and dance; he played melodeon for several morris teams in south east London, notably Blackheath Morris Men whose exploits in Charlton Park Doug described in the Charlton Parks Reminiscence Project booklet. He was always keen for Blackheath Morris Men to dance in the local area and many people will have come across them on their Boxing Day tour of Blackheath pubs, the Plumstead Make Merry and other local events as well as Charlton Park.

Doug was also musician for the Deptford Jack in the Green (http://www.deptford-jack.org.uk/) on May Day each year, which alternates between Greenwich and Deptford and the City of London. He played at English music sessions, including the Lord Hood in Creek Road and the Horseshoe in the Borough, London SE1.

His funeral was at Bratton Clovelly in Devon, his birthplace, and a celebration of his life was held at the Horseshoe in December 2012. He is much missed by his brother Bruce and family and many friends from the music and dance world. Sarah Crofts 12-3-13

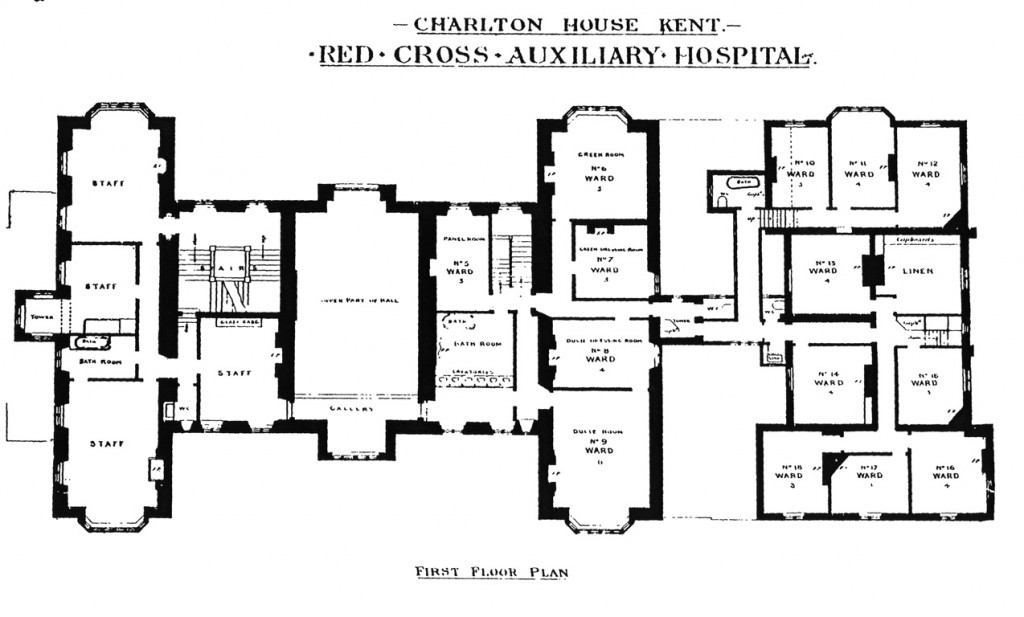

World War I

” The entry of Britain into the Great War had a tremendous effect upon family life at Charlton House, apart from the immediate response from loyal tenants and Volunteers to fight. Before the first of the casualties began to arrive at the Royal Herbert Hospital, Lady Wilson generously volunteered both her services and her home. She became deeply associated with the British Red Cross Society, and at the conclusion of hostilities was awarded the O.B.E. for her work.

In 1915 the Army (Royal Artillery) gratefully accepted the grounds of the House for use as a camp, – an extension of the horse depot established at the ‘Bull Pits’. Part of the House became an auxiliary hospital with the family residing in the nursery wing.

A typhoid epidemic that broke out at the army camp in the summer of 1916, caused great concern to Lady Wilson. Mindful of the possible effect on their young daughter, Sir Spencer and Lady Wilson chose what was intended as a temporary move to their Warwickshire home. It was a move, however that had far reaching changes, for the move became permanent and the family never returned to reside at Charlton.” John Smith. The History of Charlton.

Sir Spencer Perceval

Born in London on 1st November 1762, Spencer Perceval was the seventh son of John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont, and the second son of his father’s second marriage, to Catherine Compton.

Spencer Perceval and Charlton

Spencer Perceval was eight when his father died but he spent part of his childhood in Charlton when his father, who was First Lord of the Admiralty, was based nearby at Woolwich Dockyard. Perceval’s biographer, Gray, indicates that Perceval was christened in the parish church in Charlton. A decade later, when he and his older brother Charles rented a house nearby, they returned to visit Charlton House, by then occupied by the family of Sir Thomas Maryon-Wilson – including his daughters. Charles was attracted to Margaretta and Spencer was attracted to her younger sister Jane. With Charles now Lord Arden and seen as an eminently eligible suit for Margaretta, Sir Thomas welcomed their relationship, and they married in the chapel in Charlton House in 1787. Sir Thomas was less well disposed to the relationship between Jane and Spencer Perceval, who at that time was still a young lawyer on the Midland Circuit and of seemingly limited prospects. Nevertheless, Jane and Spencer maintained their relationship and in July 1790 contrived to marry the month after Jane became twenty-one. The two married in secret in East Grinstead on 10th August, legend has it that Jane had exited Charlton House by a rear window and was married still wearing her riding clothes. In time her family accepted the marriage, which subsequently produced six sons and six daughters. (Their story is told in Hugh Gault’s book, Living History: a family’s 19th Century– Cambridge: Gretton Books 2010). By July 1792, Perceval’s circumstances had so improved that he was able to move into a home at 59 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and eight years later had purchased the adjoining property as well.

Assassination

When Spencer Perceval was assassinated in the lobby of the House of Commons at 5.15pm on 11th May 1812, it quickly emerged that the murder was not the start of any insurrection, as was first feared, but was the act of one man, John Bellingham, a bankrupted merchant who had been imprisoned in Russia, and who felt he had been abandoned to his fate by the government. Bellingham made no attempt to escape the scene of his crime and his only defence was that he had meant to kill someone else. Although the sanity of the assassin was questioned, Bellingham was immediately placed on trial, and with it having been established that he understood the consequences of his actions, he was hanged on 15th May 1812. Perceval had died within minutes of being shot. His body was subsequently taken to 10 Downing Street and it remained there until 18th May, when the funeral procession made its way to Charlton. The funeral at St Luke’s was a private ceremony at his widow’s request.

“NEAR THIS PLACE ARE THE MORTAL REMAINS OF THE RIGHT HONORABLE SPENCER PERCEVAL, FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER WHO DIED ON THE 11TH OF MAY AD 1812 IN THE COMMONS HOUSE OF PARLIAMENT IN THE 50TH YEAR OF HIS AGE. HIS NOBLEST EPITAPH IS THE REGRET OF HIS SOVEREIGN AND HIS COUNTRY, HIS MOST SPLENDID MONUMENT THE GLORY OF ENGLAND BY HIS COUNSELS MAINTAINED, EXALTED, AMPLIFIED, BUT THE HAND OF THE ASSASSIN NOT ONLY BROKE ASUNDER THE BRILLIANT CHAINS OF DUTY WHICH BIND THE STATESMAN TO HIS NATIVE LAND AND MADE A VOID IN THE HIGH AND ELOQUENT COUNCILS OF THE NATION, IT SEVERED TIES MORE TENDER AND DELICATE, THOSE OF CONJUGAL AND PARENTAL AFFECTION, AND TURNED A HOME OF PEACE AND LOVE INTO A HOUSE OF MOURNING AND DESOLATION.”

Extract from an article written by Rick Newman, St Luke with Holy Trinity, Charlton February 2012. The full article can be found in the ‘Archive’ under ‘Articles.