Area of Interest

Barrier Gardens

Barrier Gardens consists of a flat linear north-south block of land that was at one stage occupied by the Siemens Brothers Telegraph Works. (The Factory opened in 1863, closed in 1968)

Greenwich Council identified the land as derelict in the mid-eighties and sought funding from the Greater London Council to acquire and re-landscape it. Funding was secured and Mike Tanti of Greenwich Council designed the landscaping in keeping with the new landscaping in Maryon Park.

The landscaping within Barrier Gardens consists of beds planted with native trees and shrubs and amenity grassed areas.

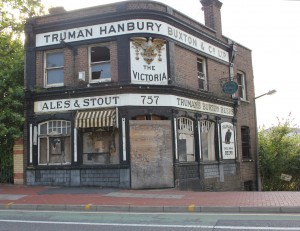

Woolwich Road by Brenda

I was born at the Woolwich Home for Mothers and Babies, Wood Street, Woolwich, which actually closed in 1984. Most all of life up until 1989 I lived at 648 Woolwich Road. My father was born just two doors away at 644 Woolwich Road, and my mother was born in Mirfield Street, which runs between Eastmoor Street and Westmoor Street, very near what is now the Thames Barrier. The terrace consisted of three storey houses originally built for the directors of Siemens, a cable factory situated on the south bank of the Thames, and the bottom of Hardens Manorway. The upstairs were very Victorian, with lovely fireplaces, coving and cornices. The ground floor originally was for the servants, and as a child I remember that both the front and back rooms of the ground floor had a cooking range at the fireplace. I had many relatives living along the terrace, aunts, uncles and cousins.

The houses to the (east/west…not sure) of Maryon Park backed on to Cox Mount. There was the ‘big hill’ and the ‘little hill’, and as a child I played on the green in front of these two ‘hills’, and also running about over them.

Behind the ‘big hill’ were sand pits, which during the 1700’s (I think) were dug out by prisoners from the prison ship that were on the River Thames. These were very dangerous and we were not supposed to play in them, and I don’t think I ever did. Before I was born though an adopted son of my parents was killed while climbing over the railings, which were supposed to keep you out of these pits.

After a couple of spells away from 648 Woolwich Road, I ended up buying the house with my husband and raised two children there. During the 80’s there was talk of demolishing the houses. I ended up chairing a campaign, not necessarily to stop this happening but to try to find out WHEN it would happen. There was so little information being given to us, but we were all suffering from the effect of this blight over our properties. There was no way any of us could sell.

We were invited to look at plans of the new road layout after the houses had been demolished, but it was a strange situation because I don’t think anyone was particularly opposed to this happening, we just wanted to be included in the run up to it so that we could plan our lives. I can’t remember there being any demonstrations against it in fact I’m sure there were none. I did address the Woolwich council debate concerning the demolition of our houses, asking that we were kept better informed. The council eventually started compulsory purchase of the houses about the mid-80’s, eventually 648 was sold to the council (I think) in about 1990/1991. To my knowledge Maryon Park is still there, it was Cox Mount that was drastically changed.

Features

Extract from ‘Public Art and the British’ by Patrick Wright. published in The Guardian Friday review, 25th August 1995

“THE REMAINS of ‘Ash Wall’, a 45-foot length of pinkish-brownish laminated glass, stands a few hundred yards from the Thames Barrier in south London. The work was commissioned in 1992 by the Public Art Development Trust, acting as agents for Greenwich Council, and took the sculptor Vong Phaophanit about a year to complete. The site was pretty run down when he began. The trees in the initial landscaping had already been damaged, but this made him all the more ambitious.

‘I knew from the beginning,’ he said, ‘that it would be a problem. But I didn’t want to accept that the idea that art shouldn’t be in a bad area, nor that it should just be about making people happy.’

Vong chose glass because he wanted to reflect the area – to catch the cars, the warehouses, and the nearby auto wrecking yards, too. He put salmon-pink silk beneath the glass panels on one side, and wood ash under the other, because they mean different things to people from different educational and cultural backgrounds………………..

To begin with, one or two panels of the glass were smashed with stones. Then the work was rammed with six-foot concrete bollards. It became routine to find rebounded rocks strewn all around it. As Vong remarked ruefully, his Ash Wall turned out to be ‘perfect for this kind of target practice’.

The work is now a dismal sight. Every one of its panels is shattered, and the rocks are still accumulating despite the high fence that surrounds the injured work. The attendants at the Thames Barrier last week described the vandalism as ‘disgusting’………………

Tension between an artwork and local taste can be constructive; but there is another view that sides with the public and expects the artist to make definite concessions. The American geographer Dolores Hayden whose new book, The Power of Place, describes a variety of projects which use public art to revive the spirits of people in inner-city areas. ‘No public art can succeed in enhancing the social meaning of place without a solid base of historical research and community support,’ she insists. The artist must leave behind ‘conventional conceptions of art as the progression of an idiosyncratic, personal style’.” The full article can be found in the archive section. Photographs are reproduced by courtesy of Colleen Chartier, Richard Waite & Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier Studio.

Extract from Interview Transcript: Bob Harris remembers the Ash and Silk Wall

(An edited audio version of this extract may also be heard below.)

The Ash and Silk Wall – a fantastic piece of work, and when I saw it it worked just right because you had to have it when the light came through it, the interplay with that sort of light coming through. I thought it was superb.

It was the first official function that I ever went to, I think, as chair of Leisure. It was something I had to defend in thinking terms. There was a lot of nervousness about it. As an idea, of course, it was Bradley’s. It was Bradley’s last period of time as the community arts development worker. I think that was one of his nominations and it was part of an Arts Council programme because they certainly sponsored it and I presume that the Barrier Park was laid out as part of the sort of community gain package around the finishing of the barrier. But I’ll never forget the night because it was… the weather was awful and Peter Columbo – who was then (presumably, I don’t know) the chairman of the Arts Council, I’m pretty sure he was – came and I remember being very nervous because this was probably my first sort of public pronunciation about anything and here was this person who had a reputation, if nothing else, and knew how to make a passionate speech and did make a passionate speech about the value, not just of the piece creatively but its setting. And I think, you know, we have to acknowledge that in all it was groundbreaking. I think what we hadn’t worked out – and I suppose I got to know quite a lot about it as I got to know more about the area – is that it had become the sort of urban area where industries had, sort of, tended to stop. They had become quite alien areas, places where people, apart from gangs, you know… but it was tragic that it was trashed. It was clearly trashed, I suspect not because of what it was but what it represented. I’m sure it was trashed because it was ‘here’s something that the council has put here.’ Which was so terribly sad. I did feel gutted when it got trashed and it got put back again and then it got trashed and then it got carted away. They didn’t tell me when they carted it away, I have to say, and put it in a skip I suspect, one of the council depots, and it was just quietly never raised again. I think that’s sad really. I suppose I feel we ought to have kept the spirit of that alive in some way. And the council’s always got to learn lessons about how it does things. It’s not the best and, maybe, it would have been better to have done a different approach but I mean, you know, it was a lovely piece of work.

Audio Extract: Bob Harris remembers the Ashen Silk Wall

Ash and Silk Wall, Project Chronology 1990 -1996.

1990 London Borough of Greenwich(LBG) is awarded Derelict Land Grant and urban funding by the Department of Environment(DoE) to create a two-acre park on disused land owned by the National Rivers Authority(NRA) between the Thames Barrier and Woolwich Road.

July 1991 Public Art Development Trust (PADT) is commissioned by LBG to provide artistic direction and implement an art programme for the new Thames barrier gardens.

November 1991 A national competition is launched to select two artists to make new works for Thames Barrier Gardens.

January – February 1992 170 artists submit proposals. Nine artists are shortlisted for interviews with PADT, LBG representatives – Bradley Hemmings, Barbara Hunt and Mike Tanti, Landscape Architect. Vong Phaophanit and Darrell Vinter are selected to produce proposals.

July 1992 The proposals are approved by PADT and LBG in consultation with NRA. The artists are commissioned to develop and cost their proposals.

October 1992 Both proposals are ambitious and large-scale, jointly exceeding the available funding. PADT and LBG agree to realise Vong Phaophanit’s Ash and Silk Wall and to seek sponsorship for Darrell Viner’s work.

November 1992 A team is assembled to work with Phaophanit: Tim MacFarlane and Brian Eckersley of Dewhurst MacFarlane as structural engineers, Paul Avery as technical construction consultant and Mark Leddra of F.A.Firman Ltd as glazing consultant. The design is developed over the next four months.

February 1993 Paul Avery is appointed as main contractor to over construction, in liaison with Vong Phaophanit.

March 1993 Structural engineer’s drawings are completed and approved by LBG and NRA. Fabrication of the structure begins off-site at F.A.Firmin’s glassworks and at Romag Security Laminators.

July 1993 Construction begins on site.

September 1993 Ash and Silk Wall is officially opened by Lord Palumbo, Chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain (now Arts Council of England) on 27th September.

October 1993 Vandals attack Ash and Silk wall with a concrete post, severely damaging one panel; the work remains structurally sound.

1994 – 1996 Despite the installation of sensory detectors and security cameras linked to NRA’s Thames barrier security station, the sculpture is continually vandalised severely damaging the glass panels. `discussions take pace between PADT, LBG and NRA to seek measures to counteract the vandalism and to determine the future of the work.

March 1996 Owing to the extent of damage, both structurally and aesthetic, Ash and Silk Wall is dismantled with the agreement of Phaophanit, PADT, LBG and NRA. Extract from ‘Documentary Notes’ by Public Art Development Trust 1996.

Flora

The wild orchid is a flower that evokes images of brilliantly sculpted colourful petals wafting their scent in far-flung exotic locations. But you needn’t go that far to see them. Surprisingly there are 56 species of this beauty just waiting to be discovered here in the UK throughout the summer months.

The Bee Orchid

Mimicking the distinctive outline of a bee, the bee orchid is possibly the UK’s most distinctively recognisable orchid. It is predominantly found on sunny, well-drained grasslands low in nutrients, although it is known to grow on heavier clay soils.